↧

The War Nerd on the Crimea crisis

↧

To err is human

I’ve rewritten The British War Office Cypher using information from TICOM report I-51 and the War Diary of Inspectorate 7/VI. I had written that the Germans were able to read this system from early 1941 till summer ’42 which was not correct. It seems that they first solved messages in summer 1941 and this was back traffic from late 1940 and early 1941. Then in the period September ’41 to January 1942 they read current traffic from the Middle East, especially during the Crusader offensive.

I have also corrected this in other essays mentioning the WOC.

↧

↧

New book on the Italian codebreakers of WWII

The book Ultra» la fine di un mito. La guerra dei codici tra gli inglesi e le marine italiane. 1934-1945-‘Ultra’ the end of a myth. The war of the codes between the British and Italian navies. 1934-1945’, by Enrico Cernuschi has been published recently.

Cernuschi is an authority on the Italian codebreakers of WWII and he has written several books on the Italian Navy. He has also co-authored with Vincent O'HaraDark Navy: The Italian Regia Marina and the Armistice of 8 September 1943 and the Naval War College Review article ‘The Other Ultra: Signal Intelligence and the Battle to Supply Rommel's Attack toward Suez’.

His new book presents the code war in the Mediterranean in a different light and points out mistakes and exaggerations in the previous accounts such as the official histories ‘British Intelligence in the Second World War’. There is information on the Italian codebreakers and their successes with Royal Navy codes as well as French, Greek, Yugoslav and USA communications. This played a role in the convoy battles as the Italians could reroute their ships once they had been sighted by enemy forces and were in danger of attack. On the other side of the hill the author points out mistakes in the standard accounts of the compromise of the German Enigma and Italian Hagelin C-38 cipher machines and their importance for the N.Africa campaign.

For this book the author has researched the British national archives and the ‘Archivio dell'Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare’ in Rome. According to him the codebreaking story in the Med must be rewritten.

Cernuschi is an authority on the Italian codebreakers of WWII and he has written several books on the Italian Navy. He has also co-authored with Vincent O'HaraDark Navy: The Italian Regia Marina and the Armistice of 8 September 1943 and the Naval War College Review article ‘The Other Ultra: Signal Intelligence and the Battle to Supply Rommel's Attack toward Suez’.

His new book presents the code war in the Mediterranean in a different light and points out mistakes and exaggerations in the previous accounts such as the official histories ‘British Intelligence in the Second World War’. There is information on the Italian codebreakers and their successes with Royal Navy codes as well as French, Greek, Yugoslav and USA communications. This played a role in the convoy battles as the Italians could reroute their ships once they had been sighted by enemy forces and were in danger of attack. On the other side of the hill the author points out mistakes in the standard accounts of the compromise of the German Enigma and Italian Hagelin C-38 cipher machines and their importance for the N.Africa campaign.

For this book the author has researched the British national archives and the ‘Archivio dell'Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare’ in Rome. According to him the codebreaking story in the Med must be rewritten.

↧

The epic quest for the Carlson-Goldsberry report

During WWII the US State Department used several cryptosystems in order to protect its radio communications from the Axis powers. For low level messages the unenciphered Gray and Brown codebooks were used. For important messages four different codebooks (A1,B1,C1,D1) enciphered with substitution tables were available.

In response two cryptanalysts were sent from the US to evaluate the compromise of US codes in more detail. They were Paavo Carlson of the Army’s Signal Security Agency-SSA and Paul E. Goldsberry of the State Department’s cipher unit. Their report dated 23 November 1944 had details on the solution of US systems.

Unfortunately finding this report has proven to be quite a problem!

They also gave me a reference to an OSS report in the Director’s files but I had already checked that.

Their most modern and (in theory) secure system was the M-138-A strip cipher. Unfortunately for the Americans this system was compromised and diplomatic messages were read by the Germans, Finns, Japanese, Italians and Hungarians. The strip cipher carried the most important diplomatic traffic of the United States (at least until late 1944) and by reading these messages the Axis powers gained insights into global US policy.

Germans, Finns and Japanese cooperated on the solution of the strip cipher. The Japanese gave to the Germans alphabet strips and numerical keys that they had copied from a US consulate and these were passed on by the Germans to their Finnish allies. Then in 1943 the Finns started sharing their results with Japan. The German effort

Unfortunately the information we have today on the compromise of the State Department’s strips cipher is limited. One problem is that the archives of the agencies that worked on this system are not available to researchers. Three different German agencies worked on the US diplomatic M-138-A strip cipher. The German High Command’s deciphering department – OKW/Chi, the Foreign Ministry’s deciphering deparment Pers Z and the Air Ministry’s Research Department - Reichsluftfahrtministerium Forschungsamt. I know that the NSA has some interesting reports on the codebreaking successes of the Forschungsamt but they have not been declassified yet. Regarding OKW/Chi I don’t know if their archives (or parts of them) survived the war. Finally the files of the Pers Z agency were captured by the Anglo-Americans at the end of the war but the reports I’ve seen from the National Archives and Records Administration are mostly administrative files.

This means that so far our sources on the strip compromise are mainly TICOM reports written postwar.The Finnish codebreakers and the strip cipher

The Finnish codebreakers also worked on the strip cipher and solved several links in the period 1942-44. In this area there was cooperation with their German counterparts, not only in receiving copies of the Japanese cipher material but also exchanges of personnel and analysis of the strip system.The fact that the Finns cooperated with the Germans against this cryptosystem means that we can find out more about the German operation through Finnish sources and thus circumvent the lack of German archival sources.

Operation Stella PolarisIn September 1944 Finland signed an armistice with the Soviet Union. The people in charge of the Finnish signal intelligence service anticipated this move and fearing a Soviet takeover of the country had taken measures to relocate the radio service to Sweden. This operation was called Stella Polaris (Polar Star).

In late September roughly 700 people, comprising members of the intelligence services and their families were transported by ship to Sweden. The Finns had come to an agreement with the Swedish intelligence service that their people would be allowed to stay and in return the Swedes would get the Finnish crypto archives and their radio equipment. At the same time colonel Hallamaa, head of the signals intelligence service, gathered funds for the Stella Polaris group by selling the solved codes in the Finnish archives to the Americans, British and Japanese. The Stella Polaris operation was dependent on secrecy. However the open market for Soviet codes made the Swedish government uneasy. In the end most of the Finnish personnel chose to return to Finland, since the feared Soviet takeover did not materialize. The American reaction and the Carlson-Goldsberry report

According to the NSA study History of Venona (Ft. George G. Meade: Center for Cryptologic History, 1995) by Robert Louis Benson and Cecil J. Phillips, it was at that time that the Finns revealed to the US authorities that they had solved their diplomatic codes. On 29 September 1944 colonel Hallamaa met with L.Randolph Higgs of the US embassy in Stockholm and told him about their success.In response two cryptanalysts were sent from the US to evaluate the compromise of US codes in more detail. They were Paavo Carlson of the Army’s Signal Security Agency-SSA and Paul E. Goldsberry of the State Department’s cipher unit. Their report dated 23 November 1944 had details on the solution of US systems.

Freedom of Information Act requests

After trying to find this report in the US archives i gave up and filed FOIA requests with the State Department, NSA and NARA. The results:1). The State Department told me that they no longer have these files as they have been sent to NARA so I should bother them.

2). NARA could not locate this file but they did send me a list of references that I should look up. 3). The NSA informed me that they had expended the free time allowed for research and if I wanted to continue I’d have to pay. I decided not to.

Assistant Secretary ShawApart from the FOIA requests I tried to find information on the people responsible for evaluating the compromise of State Department codes during the war. A name that came up in relevant reports was Assistant Secretary Shaw. This was Gardiner Howland Shaw, Assistant Secretary of State in the period 1941-44 and in charge of the State Department’s cipher unit. Unfortunately NARA does not have a separate body of records for G. Howland Shaw.

Another lead I followed was the Shaw foundationbut their response was that ‘To our knowledge, he left no immediate family members and we have no record of any of his State Dept work.’The messages from the embassy in Sweden

After failing to find anything either with the FOIA requests or the Shaw search I decided it would be best to try to track down the messages sent from the US embassy Sweden to Washington during the days mentoned in ‘History of Venona’. Unfortunately the State Department messages are indexed according to a complicated system and it is very difficult to find anything:So I asked NARA again if they could locate the messages of the embassy in Sweden for these specific dates and their response was:

‘We searched the Source Cards, 1940-1944; General Records of the Department of State, Record Group 59 and located index cards which lead us to believe that no record of these sensitive meetings/topics were kept by the State Department. It is possible, though, that further examination of this series may yield records which may be pertinent to your research.’Now I have to give credit where credit is due and the NARA people really did some great work in this case! Unfortunately even after all these efforts the Carlson-Goldsberry report continues to elude us…

A small win?Although I haven’t been able to find the actual report I think that a page found in NARA-RG 457-Entry 9032-box 214-‘M-138-A numerical keys/daily key table/alphabet strips’ is a part of that report or at least contains information from it.

↧

Some thoughts on Soviet tank reliability in WWII

The Eastern front was the largest land campaign of WWII and millions of soldiers fought and died there in the period 1941-45. Although infantry dominated the fighting both sides used a large number of tanks and armored vehicles and these played a big role in breakthrough operations. Most historians focus on the ‘paper’ characteristics of tanks and the production statistics however a very important aspect of complex weapon systems is their reliability and kill/loss ratio. In the East the Germans were always outnumbered but the exchange ratios were in their favor. I’ve often wondered of how much that has to do with poor reliability of Soviet equipment.

Here is something I read recently from ‘Moscow to Stalingrad: Decision in the East’ by Earl F. Ziemke, in page 363:

Active as it was, the Soviet armor was apparently not giving fully satisfactory performance at this stage, and in early August, it became the subject of the following Stalin order: ‘Our armored forces and their units frequently suffer greater losses through mechanical breakdowns than they do in battle. For example, at Stalingrad Front in six days twelve of our tank brigades lost 326 out of their 400 tanks. Of those about 260 owed to mechanical problems. Many of the tanks were abandoned on the battlefield. Similar instances can be observed on other fronts. Since such a high incidence of mechanical defects is implausible, the Supreme Headquarters sees in it covert sabotage and wrecking by certain elements in the tank crews who try to exploit small mechanical troubles to avoid battle.’

Henceforth, every tank leaving the battlefield for alleged mechanical reasons was to be gone over by technicians, and if sabotage was suspected, the crews were to be put into tank punishment companies or "degraded to the infantry" and put into infantry punishment companies.'"Were the problems really caused by sabotage and wreckers? Apparently not, since captured T-34 tanks used by the Germans in summer 1944 had the following problems:

‘Regardless of our limited experience, it can be stated that the Russian tanks are not suitable for long road marches and high speeds. It has turned out that the highest speed that can be achieved is 10 to 12 km/hr. It is also necessary on marches to halt every half hour for at least 15 to 20 minutes to let the machine cool down. Difficulties and breakdowns of the steering clutches have occurred with all the new Beute-Panzer. In difficult terrain, on the march, and during the attack, in which the Panzer must be frequently steered and turned, within a short time the steering clutches overheat and are coated with oil. The result is that the clutches don't grip and the Panzer is no longer maneuverable. After they have cooled, the clutches must be rinsed with a lot of fuel.’Also T-34 tanks captured by the Americans in Korea (built in 1945) continued to suffer from the same issues. According to Zaloga’s ‘T-34-85 Medium Tank’, p21-22

An analysis of a T-34-85 captured in Korea by the American tank producer Chrysler, conducted in 1951, provides a good assessment of the T-34- 85……………………. The study, found the following negative features about the tank:…………………………………. Wholly inadequate engine intake air cleaners could be expected to allow early engine failure due to dust intake and the resulting abrasive wear. Several hundred miles in very dusty operation would probably be accompanied by severe engine power loss.' The report was also critical of the lack of a turret basket, poor fire fighting equipment, poor electrical weatherproofing, lack of an auxiliary generator to keep the batteries charged, and lack of a means to heat engine oil for cold weather starts. The report noted that although Soviet manufacturing techniques were adequate for the job, there were many instances where poor or unskilled workmanship undermined the design, and where overworked machines led to course feeds, severe chatter or tearing of machined surfaces, a consequence no doubt of the extreme pressures placed on plants to ensure maximum output. For example, in the tank inspected (manufactured in 1945) the soldering job on the radiator was so poor that it effectively lost half of its capacity.It’s also worth noting that even in 1941 German reports on captured Soviet T-26 and BT tanks pointed out serious productions issues. For the T-26 tank: ‘The Pz.Kpfw.Zug created by the division is no longer operational. One Panzer is completely burnt out due to an engine fire. Both of the other Panzers have engine and transmission problems. Repetitive repairs were unsuccessful. The Panzers always broke down after being driven several hundred meters on good roads. As reported by technical personnel, both of the engines in the Panzers are unusable because they were incorrectly run in.’

And for the BT tank: ‘B. T. (Christi): The main cause of failure is a transmission that is too weak in combination with a strong engine that should provide the tank with high speed, but is over-stressed when driven off road where the lower gears must be used for longer periods. In addition, as in the T 26, problems continuously arise that are due to entire design and poor materials, such as failure of the electrical system, stoppages in fuel delivery, breaks in the oil circulation lines, etc.’Finally there are the Aberdeen tests on a T-34 tank:

'On the T-34 the transmission is also very poor. When it was being operated, the cogs completely fell to pieces (on all the cogwheels). A chemical analysis of the cogs on the cogwheels showed that their thermal treatment is very poor and does not in any way meet American standards for such mechanisms.’‘The deficiency of our diesels is the criminally poor air cleaners on the T-34. The Americans consider that only a saboteur could have constructed such a device’

The reliability issues of Soviet tanks during WWII point to serious problems with Soviet industry. The only other explanation is that a huge Nazi/White Guard wrecker movement existed in Soviet factories…I think that even comrade Stalin would find this idea implausible!

↧

↧

Update

I have added information and pics in The US TELWA code.

↧

Soviet cryptologic security failures in WWII – A sneak peak

I’ve already covered the cryptologic failures of the United States and Britainin WWII but I still haven’t covered the Soviet Union. According to Soviet/Russian sources their codes were impenetrable and the Germans were never able to compromise their high level communications links. Is that true?

Well I’m still researching this case and I haven’t copied all the available documents. Once I do I will write a detailed essay on Soviet codes.

For now here is a sneak peak:

Well I’m still researching this case and I haven’t copied all the available documents. Once I do I will write a detailed essay on Soviet codes.

For now here is a sneak peak:

↧

NSA in the news - yet again!

↧

Heartbleed bug and OSS codes

The recently discovered Heartbleedbug is considered to be one of the worst compromises of internet security, so check to see if the websites that you’re using have fixed it and change your passwords.

I have added information and pics in Allen Dulles and the compromise of OSS codes in WWII.

↧

↧

Soviet pre-arranged form reports

The war between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union was the largest land campaign of WWII, with millions of troops fighting in the vast areas of Eastern Europe. In this conflict both sides used every weapon available to them, from various models of tanks and self propelled guns to fighter and bomber aircraft. However an aspect of the war that has not received a lot of attention from historians is the use of signals intelligence and codebreaking by the Germans and the Soviets.

By analyzing this information the Germans were not only able to monitor the strength and equipment situation of enemy units but also make deductions about overall Soviet strategy.

Codebreaking and signals intelligence played a major role in the German war effort. The German Army had 3 signal intelligence regiments (KONA units) assigned to the three Army groups in the East (Army Group North, South and Centre). In addition from 1942 another one was added to monitor Partisan traffic. The Luftwaffe had similar units assigned to the 3 Air Fleets (Luftflotten) providing aerial support to the Army Groups. Both the Army and the Luftwaffe also established central cryptanalytic departments (Horchleitstelle Ost and LN Regt 353) for the Eastern front in East Prussia. During the war this effort paid off as the German codebreakers could solve Soviet low, mid and high level cryptosystems. They also intercepted the internal radio teletype network carrying economic and military traffic and used traffic analysis and direction finding in order to identify the Soviet order of battle.

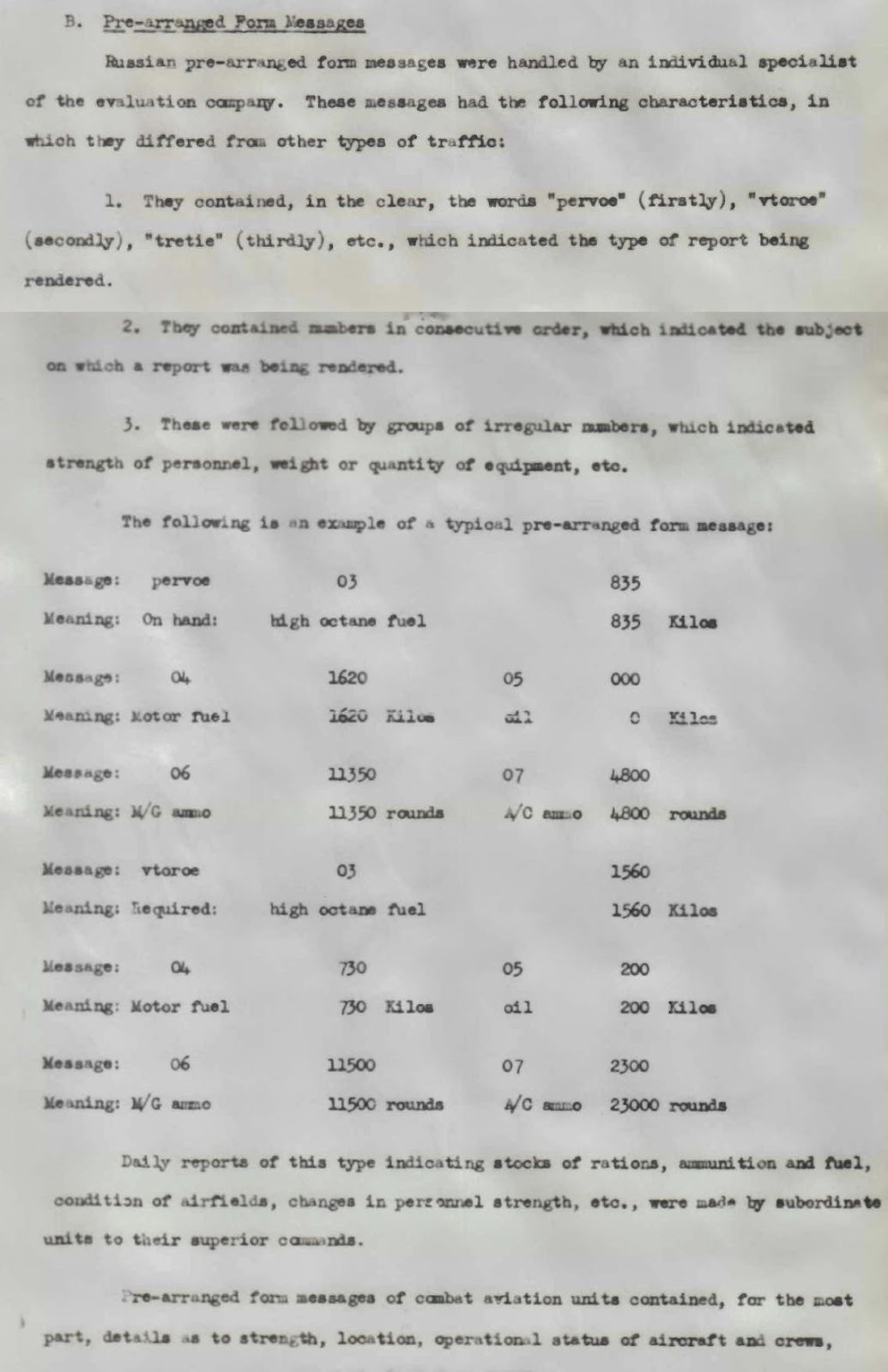

An important source of information on the Soviet military was their pre-arranged form reports sent at regular intervals by all units to their higher headquarters. These messages used a pre-arranged format to communicate strength, serviceability and loss statistics. By reading these messages the Germans were able to monitor the strength, losses and reinforcements of Soviet formations.Luftwaffe Chi Stelle effort

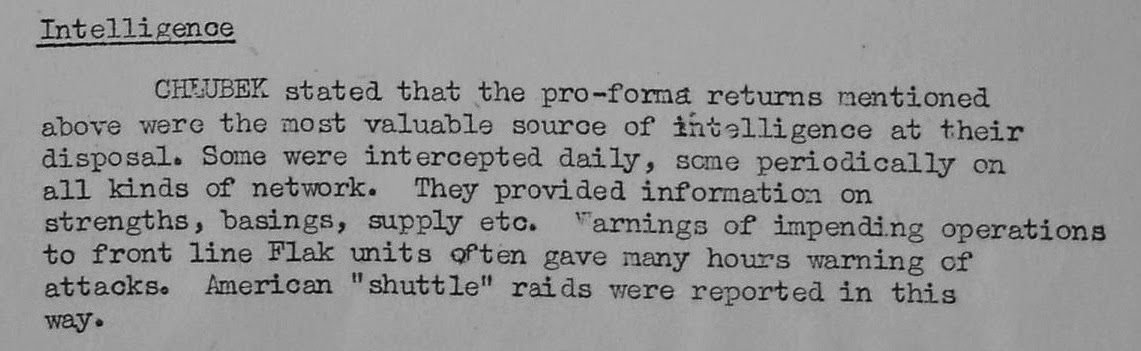

Several TICOM sources give information on the exploitation of these pre-arranged reports by the codebreakers of the Luftwaffe. According to IF-187 Seabourne Report, Vol. XII. ‘Technical Operations in the East, Luftwaffe SIS’ (available from site Ticom Archive) pages 5-8 the reports had information on the condition of Soviet airfields, stocks of planes, ammunition, rations and fuel.TICOM report I-107 ‘Preliminary Interrogation Report on Obltn. Chlubek and Lt. Rasch, both of III/LN. RGT. 353’, p4 says that the pre-arranged reports were extremely valuable to the Luftwaffe.

Army’ s General der Nachrichten Aufklaerung effort

According to FMS P-038 'German Radio intelligence', p115-7 pre-arranged reports sent by Soviet Army units contained information on personnel strength, losses, number of vehicles, guns, ammunition gasoline supplies and similar statistical data. ↧

Typex cipher machines for the Polish Foreign Ministry

In 1926, the British Government set up an Inter-Departmental Cypher Committee to investigate the possibility of replacing the codebooks then used by the armed forces, the Foreign Office, the Colonial Office and the India Office with a cipher machine. It was understood that a cipher machine would be inherently more secure and much faster to use in encoding and decoding messages. Despite spending a considerable amount of money and evaluating various models by 1933 the committee had failed to find a suitable machine. Yet the need for such a device continued to exist and the Royal Air Force decided to independently fund such a project. The person in charge of their programme was Wing Commander Lywood, a member of their Signals Division. Lywood decided to focus on modifying an existing cipher machine and the one chosen was the commercially successful Enigma. Two more rotor positions were added in the scrambler unit and the machine was modified so that it could automatically print the enciphered text. This was done so these machines could be used in the DTN-Defence Teleprinter Network.

The new machine was called Typex (originally RAF Enigma with TypeX attachments). In terms of security it was similar to a commercial Enigma but had the additional security measure of multiple notches per rotor. This meant that during encipherment the rotors moved more often than in the standard Enigma machines.

In the period 1939-45 the Typex was one of the main high level British crypto systems. According to documents found in British national archives HW 40/221 ‘Poland: reports and correspondence relating to the security of Polish communications’, it seems that the Polish government in exilelearned about Typex and was interested in buying a small number of machines in 1944.During WWII the Polish foreign ministry relied on enciphered codebooks for its secret communications. Perhaps they were interested in Typex because they considered their own systems insecure. Whatever the reason it doesn’t seem like they were given any machines since the report says ‘the supply position in respect of Type X is such that it is probably impossible to meet their requirements for the time being’

It is interesting to note that the same report says ‘provided the Type X machines supplied were not fitted with Plugboard and provided also we wired for them and supplied the necessary drums, the advantages to be gained by meeting their request would outweigh the disadvantages’.Hmmm…..

↧

Australian codebreakers of WWII

The very interesting book ‘Breaking Japanese Diplomatic Codes David Sissons and D Special Section during the Second World War’ is available for download from the Australian National University’s website.

The summary says:

During the Second World War, Australia maintained a super-secret organisation, the Diplomatic (or `D’) Special Section, dedicated to breaking Japanese diplomatic codes. The Section has remained officially secret as successive Australian Governments have consistently refused to admit that Australia ever intercepted diplomatic communications, even in war-time.This book recounts the history of the Special Section and describes its code-breaking activities. It was a small but very select organisation, whose `technical’ members came from the worlds of Classics and Mathematics. It concentrated on lower-grade Japanese diplomatic codes and cyphers, such as J-19 (FUJI), LA and GEAM. However, towards the end of the war it also worked on some Soviet messages, evidently contributing to the effort to track down intelligence leakages from Australia to the Soviet Union.

This volume has been produced primarily as a result of painstaking efforts by David Sissons, who served in the Section for a brief period in 1945. From the 1980s through to his death in 2006, Sissons devoted much of his time as an academic in the Department of International Relations at ANU to compiling as much information as possible about the history and activities of the Section through correspondence with his former colleagues and through locating a report on Japanese diplomatic codes and cyphers which had been written by members of the Section in 1946. Selections of this correspondence, along with the 1946 report, are reproduced in this volume. They comprise a unique historical record, immensely useful to scholars and practitioners concerned with the science of cryptography as well as historians of the cryptological aspects of the war in the Pacific.↧

The Japanese J-19 FUJI code

In order to protect its diplomatic communications Japan’s Foreign Ministry used several cryptologic systems during WWII. In 1939 the PURPLE cipher machine was introduced for the most important embassies, however not all stations had this equipment so hand systems continued to play an important role in the prewar period and during the war.

Once the messages were encoded using the J-19 code table then they had to be enciphered. There were two cipher procedures used with the J-19, substitution and transposition.

One of the main hand systems was the J-19 code, enciphered either with bigram substitution tables or with transposition using a stencil.

Historical overviewThe fist Japanese diplomatic system identified by US codebreakers was introduced during WWI and it was a simple bigram code called ‘JA’. There were two code tables, one of vowel-consonant combinations and the other of consonant vowel. Similar systems, some with 4-letter code tables were introduced in the 1920’s.

These unenciphered codes were easy to solve simply by taking advantage of the repetitions of the codegroups of the most commonly used words and phrases. US codebreakers solved these codes and thus learned details of Japan’s foreign policy. During the Washington Naval Conference the codebreakers of Herbert Yardley’sBlack Chamber were able to solve the Japanese code and their success allowed the US diplomats to pressure the Japanese representatives to agree to a battleship ratio of 5-5-3 for USA-UK-Japan. However this success became public knowledge when in 1931 Yardley published ‘The American Black Chamber’, a summary of the codebreaking achievements of his group. The book became an international best seller and especially in Japan it led to the introduction of new, more secure cryptosystems.In the 1930’s the Japanese Foreign Ministry upgraded the security of its communications by introducing the RED and PURPLE cipher machines and by enciphering their codes mainly with transposition systems.

J-19 FUJI code

The J-19 code had bigram and 4- letter code tables similar to the ones used previously by the Japanese Foreign Ministry. According to the NSA study ‘West Wind Clear: Cryptology and the Winds Message Controversy A Documentary History’ it was used from 21 June 1941 till 15 August 1943. In terms of security the J-19 FUJI and the similar codes J-16 MATSU to J-18 SAKURA, that preceded it in the period 1940-41, were much more sophisticated than the older Japanese diplomatic systems. They had roughly double the number of code groups at ~1.600 bigram entries and in addition there was a 4-letter table with 900 entries for ‘common foreign words, usually of a technical nature, proper names, geographic locations, months of the year, etc’.

Example of the code table from ‘West Wind Clear’:Once the messages were encoded using the J-19 code table then they had to be enciphered. There were two cipher procedures used with the J-19, substitution and transposition.

CIFOL VEVAZ substitution

J-19 messages with the indicators CIFOL or VEVAZ were enciphered using bigram substitution tables. A random letter sequence was coupled with the coded text and each pair of letters was substituted using the substitution table. According to the NSA study this cipher procedure was rarely used.Columnar transposition using a stencil

The basic cipher system used with the J-19 code was columnar transposition based on a numerical key, with a stencil being used for additional security. The presence of ‘blank’ cages in the box created irregular lengths for each column of the text. Three different stencils were used each month with each being valid for 10 days. The numerical key changed daily. There were four different settings for the J-19 system: General, Europe, America and Asia.Examples from ‘West Wind Clear’:

Importance of the J-19 FUJI code

The J-19 code was important enough for both the Allies and the Axis to devote significant resources in solving it, even going so far as to build special cryptanalytic equipment. The reason they went through all this trouble is that during the war only a small number of Japanese embassies had the PURPLE cipher machine so the rest had to rely on hand systems and one of the main diplomatic codes was the J-19 FUJI. Intercepted diplomatic traffic from around the world on this system carried economic, political, military and secret intelligence information. A special case was the Moscow embassy (moved to Kuibyshev during the war) and their use of the J-19 for communications with Tokyo. It seems that this embassy was either not given a PURPLE machine or perhaps they had to dismantle it in 1941, so they relied on the J-19 for their most important messages. During WWII Japan fought on the side of the Axis but was careful to avoid a confrontation with the Soviet Union. War between the SU and Japan finally broke out in August 1945 but during the period 1941-45 Japanese diplomats were free to collect and transmit important information from the SU on military and political developments as well as their discussions and negotiations with Soviet officials. These messages were a prime target for the Allied and German codebreakers.

Allied exploitation of the improved J series codesWhen the new code J-16 MATSU was introduced in August 1940 it proved much harder to solve that the previous Japanese systems. A team of cryptanalysts of the Army’s Signal Intelligence Service, led by Frank Rowlett analyzed this traffic and came to the conclusion that it was a bigram code enciphered with a transposition key. Rowlett realized that this system was similar to the German ADFGVX cipher of WWI that they had already researched extensively as part of their training program. Their effort to solve this Japanese code had not progressed much when they were given copies of the code, the stencils and some of the numerical keys. These had been copied by US Naval Intelligence from a Japanese embassy or consulate in the US. Thanks to these specimens Rowlett’s work became much easier and messages could be read. Changes in the code could be followed by taking advantage of operator mistakes.

From the 1974 interview of Frank Rowlett, pages 25-28:It is interesting to note that before they solved this code the head of the codebreaking department, William Friedman was very pessimistic about the prospects of success.

During the war traffic on this system increased significantly and the solution of the daily changing settings became a problem for the small group of personnel, so there was an effort to automate the process. The device built was an attachment for standard IBM punch card equipment called the ‘Electromechanagrammer’ or ‘Gee-Whizzer’.

According to the NSA study ‘It Wasn’t All Magic: The Early Struggle to Automate Cryptanalysis, 1930s – 1960s’, p50-51:

‘The Gee Whizzer had been the first to arrive. In its initial version it did not look impressive; it was just a box containing relays and telephone system type rotary switches. But when it was wired to one of the tabulating machines, it caused amazement and pride. Although primitive and ugly, it worked and saved hundreds of hours of dreadful labor needed to penetrate an important diplomatic target. It proved so useful that a series of larger and more sophisticated "Whizzers" was constructed during the war……………….When the Japanese made one of their diplomatic "transposition" systems much more difficult to solve through hand anagramming (reshuffling columns of code until they made "sense"), the American army did not have the manpower needed to apply the traditional hand tests.Friedman's response was to try to find a way to further automate what had become a standard approach to mechanically testing for meaningful decipherments……………………………………..Rosen and the IBM consultants realized that not much could be done about the cards; there was no other viable memory medium. But it was thought that it might be possible to eliminate all but significant results from being printed. Rosen and his men, with the permission and help of IBM, turned the idea into the first and very simple Gee Whizzer. The Whizzer's two six-point, twenty-five-position rotary switches signalled the tabulator when the old log values that were not approaching a criterion value should be dropped from its counters. Then they instructed the tabulator to start building up a new plain-language indicator value.

Simple, inexpensive, and quickly implemented, the Gee Whizzer reinforced the belief among the cryptoengineers in Washington that practical and evolutionary changes were the ones that should be given support.’Australian effort

The American codebreakers were not the only ones who were regularly reading this system. Their British allies were also exploiting the J-19 and in Australia a small group called Diplomatic Special Sectionsolved several Japanese diplomatic codes. According to the book ‘Breaking Japanese Diplomatic Codes David Sissons and D Special Section during the Second World War’, p62 the J-19 was the main Japanese diplomatic code used in the period 1941-43.The solution of the traffic on the Kuibyshev–Tokyo link was one of their main commitments and in page 38 it says:

‘The report alludes, very briefly, to the high intelligence value of the intercepts of the telegrams exchanged between the Japanese Foreign Ministry and its Ambassador in Russia, Sato Naotake.It seems that in its coverage of the Kuibyshev–Tokyo–Kuibyshev circuit, the Section was able to provide strategic intelligence of value.’

German exploitation of J-19 codeForeign diplomatic codes were worked on by three different German agencies, the German High Command’s deciphering department – OKW/Chi, the Foreign Ministry’s deciphering deparment Pers Z and the Air Ministry’s Research Department - Reichsluftfahrtministerium Forschungsamt.

From postwar TICOM reports it is clear that these agencies worked on the J-19 with success but not many details are available on their operations. At this time there is very limited information available on the work of the Forschungsamt. EASI vol7, p82 says that they worked on ‘a transposition with nulls over two and four letter code’. This was clearly either the J-19 or one of the similar J series systems.

At Pers Z it seems they solved it regularly in the period 1941-43. EASI vol6, p29 says:‘A major diplomatic code (known to the Germans as JB-57) was solved at the end of 1941 and read currently for about two years. This was a two-four letter book, enciphered by a series or alphabets and/or stencil transposition with nulls.’

The Germans were very interested in the messages from the embassy in the SU and according to David Kahn’s ‘The codebreakers’, p444:‘the subsequent solutions provided the Germans with information about Russian war production and army activities’

At OKW/Chi they not only solved this code but also built a specialized cryptanalytic device called the ‘Bigram search device’ (bigramm suchgerät) for recovering the daily settings. EASI vol3, p65 says:‘FUJI, a transposition by means of a transposition square with nulls applied to a two and four letter code. This system was read until it ended in August, 1943. It was broken in a very short time by the use of special apparatus designed by the research section and operated by Weber. New traffic could be read in less than two hours with the aid of this machine.’

The ‘Bigram search device’ is called ‘digraph weight recorder’ in the US report ‘European Axis Signal Intelligence in World War II’ volume 2. In pages 51-53 details are given on the operation of this device:‘The digraph "weight" recorder consisted of: two teleprinter tape reading heads, a relay-bank interpreter circuit, a plugboard ‘’weight’’ assignor and a recording pen and drum.

Each head read its tape photoelectrically, at a speed of 75 positions per second.’The machine could find a solution in less than two hours and did the work of 20 people, thus saving manpower.

How did the German machine compare with the American ‘Gee-Whizzer’? European Axis Signal Intelligence in World War II’ volume 2 points out the differences in their operation and the pros and cons of each device:

‘If the sections of text chosen from any given message were well chosen from a cryptanalytic viewpoint, the American machine proved much faster than the German machine, because the print of totals was easier for the cryptanalyst to analyze than just the individual values listed by the German machine; but if the sections of text were not well chosen and no true columns were included in the choice, then the German machine ,had the advantage since it recorded all possible juxtapositions quickly, and all true matches were included in the data.’Sources: ‘European Axis Signal Intelligence in World War II’ volumes 2,3,6,7 , TICOM reports I-22, I-25, I-37, I-90, I-124, I-150, DF-187B , ‘The Codebreakers’, ‘Breaking Japanese Diplomatic Codes David Sissons and D Special Section during the Second World War’, United States Cryptologic History Series IV: World War II Volume X: ‘West Wind Clear: Cryptology and the Winds Message Controversy A Documentary History’, United States Cryptologic History, Special Series, Volume 6, ‘It Wasn’t All Magic: The Early Struggle to Automate Cryptanalysis, 1930s – 1960s’, NSA interviews of Frank Rowlett 1974

↧

↧

Update

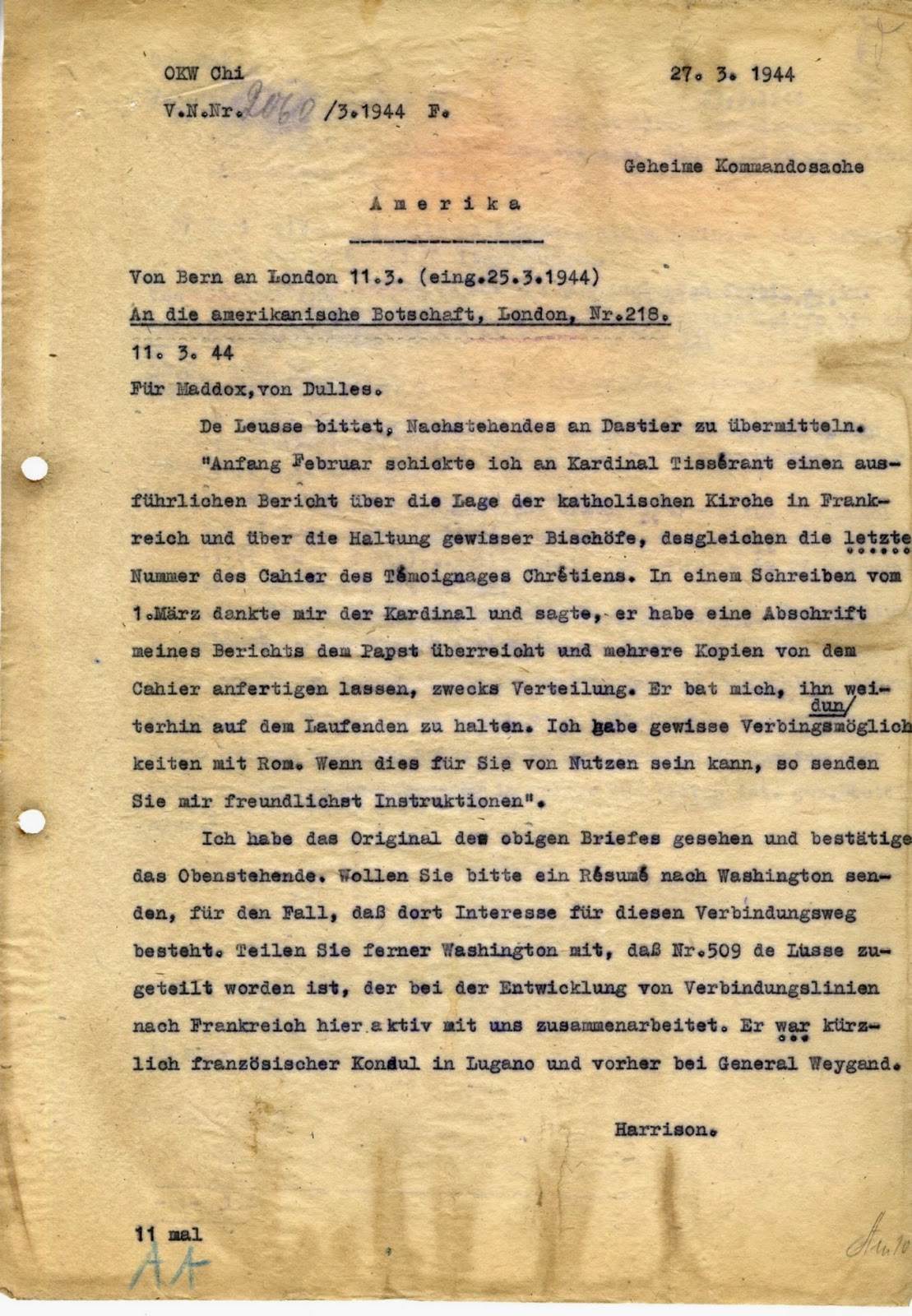

I have added a decoded message from the Bern OSS station in Allen Dulles and the compromise of OSS codes in WWII. This confirms the German statements that they could read OSS communications during WWII.

↧

Compromise of the State Department’s strip cipher in 1944

During WWII the US State Department used several cryptosystems in order to protect its radio communications from the Axis powers. For low level messages the unenciphered Gray and Brown codebooks were used. For important messages four different codebooks (A1,B1,C1,D1) enciphered with substitution tables were available. Their most modern and (in theory) secure system was the M-138-A strip cipher. Unfortunately for the Americans this system was compromised and diplomatic messages were read by the Germans, Finns, Japanese, Italians and Hungarians. The strip cipher carried the most important diplomatic traffic of the United States (at least until late 1944) and by reading these messages the Axis powers gained insights into global US policy.

A. Diplomatic - most of the American strip cipher was read, strip cipher was used by the military as well as by the diplomatic.’

Messages between embassies should have been on the ‘circular’ strips. Messages to or from Washington should have been sent on the ‘special’ strips. From the TICOM reports and the few messages found in boxes 205-213 it is clear that the German codebreakers were able to solve the strip cipher even as late as 1944 and that included both the ‘circular’ messages and at least some of the ‘specials’.

In addition there is in these boxes a list with the code L-1456 vol VIII that according to NARA ‘does not appear to be linked to the other documents’. It is possible that it has some connection to the M-138-A case.

The strip cipher was not a weak system cryptologically, even though it could not offer the security of cipher machines. The success of German and Finnish codebreakers was facilitated in many cases by the poor way that the system was used by the State Department.

M-138-A strip cipherThe M-138-A system consisted of an aluminum frame (or later wooden/plastic) with room for 25 or 30 paper strips. Each strip had a random alphabet. The daily key specified the strips to be inserted and the order that they were to be inserted in. The plaintext was written vertically at the first column by rearranging the strips. Then another column was selected to provide the ciphertext.

The way the system worked was that each day 30 alphabet strips were chosen out of the available 50 (both for the ‘circulars’ and the ‘specials’). The strips used and the order that they were inserted in the metal frame was the ‘daily key’. The strip system did not have a separate ‘key’ for each day. Instead there were only 40 different rearrangements.

German efforts to solve the US diplomatic strip cipherThree different agencies worked on the US diplomatic M-138-A strip cipher. The German High Command’s deciphering department – OKW/Chi, the Foreign Ministry’s deciphering deparment Pers Z and the Air Ministry’s Research Department - Reichsluftfahrtministerium Forschungsamt.

At the Forschungsamt some work was done on the strip but apart from the fact that they solved some traffic we don’t know any more details. At OKW/Chi an entire team worked on the strip, led by the mathematician Wolfgang Franz and they built a specialized cryptanalytic device called ‘Tower clock’ (Turmuhr). This device was a ‘statistical depth-increaser’ according to US reports.

At Pers Z they devoted significant resources against the strip cipher. A team of mathematicians, led by Professor Hans Rohrbach made extensive use of IBM/Hollerith punch card equipment in their efforts to solve the alphabet strips and also built a special decoding device called ‘Automaton’.Proof of OKW/Chi success in 1944

The information given by Wolfgang Franz who was interrogated in 1949 is limited. In his report DF-176 he said in pages 6-9:‘Especially laborious and difficult work was connected with an American system which, judging by all indications was of great importance. This was the strip cipher system of the American diplomatic service which was subsequently solved in part.’

‘All told, some 28 circuits were solved at the Bureau under my guidance, likewise six numerical keys-some of them only in part.’A matter of some controversy is the extent of success they had in 1944 against this system. The head of the mathematical research department of OKW/Chi, Dr Erich Huettenhain said in TICOM I-2 ‘Interrogation of Dr. Huettenhain and Dr. Fricke at Flensburg, 21 May 1945’, p2:

‘Q. What work was done on British and American codes and ciphers?A. Diplomatic - most of the American strip cipher was read, strip cipher was used by the military as well as by the diplomatic.’

However in TICOM I-145 ‘Report on the US strip system by Reg Rat Dr Huettenhain’ he stated:

‘Only a little of the material received could be read at once. Generally it was back traffic that was read. As, however, the different sets of strips were used at different times by other stations, it was possible, in isolated cases, to read one or the other of the special traffics currently. We are of opinion that of the total material received, at the most one fifth was read, inclusive of back traffic. None was read after the beginning of 1944.’This seems to be at odds with the version given by the same person in an unpublished manuscript written in 1970 in which he said:

‘Auf diese Weise wurden von 1942 bis September 1944 insgesamt 22 verschiedene Linien und alle cq-Sprüche mitgelesen’Translation: In this way, were read by 1942 to September 1944, a total of 22 different links and all cq (call to quarters) messages. (note that cq messages means ‘circulars’)

Were the Germans able to solve the State Department’s high level messages in 1944? The answer is yes. In the US National Archives, in collection RG 457 ‘Records of the National Security Agency’ - Entry 9032 - boxes 205-213 ‘German decrypts of US diplomatic messages 1944’ one can find many decoded messages from US embassies and consulates around the world. Many have a note on the lower right side identifying the cryptosystem used. The German code for the strip cipher was Am10. This is mentioned in TICOM I-145 which says ‘The American strip system Am10’ and in TICOM DF-176, p7: ‘the Am10-that was the designation of the strip cipher system’.

In these boxes there are a few messages with the tag Am10 sent in 1944 and decoded in that year. They prove that the Germans could solve the strip system even in 1944. Here are four of these messages:From box 209 – Bern-London

From box 209 - Algiers

From box 212 – Madrid-Washington

Messages between embassies should have been on the ‘circular’ strips. Messages to or from Washington should have been sent on the ‘special’ strips. From the TICOM reports and the few messages found in boxes 205-213 it is clear that the German codebreakers were able to solve the strip cipher even as late as 1944 and that included both the ‘circular’ messages and at least some of the ‘specials’.

In addition there is in these boxes a list with the code L-1456 vol VIII that according to NARA ‘does not appear to be linked to the other documents’. It is possible that it has some connection to the M-138-A case.

Acknowledgements: I have to thank Randy Rezabek of TICOM Archive for collaborating with me on this research project and covering parts of the cost and also my researcher Mike Constandy of Westmorland Research for going though the boxes and finding needles in a haystack.

↧

Tanks, tanks, tanks

1). I’m going to write something on the USM4 Sherman tankand whether it was a deathtrap or a war-winner (or somewhere in between).

2). Wait what’s this? Another report on theBest tank of WWII, ehm I mean the Soviet T-34 tank? Hmmm I guess I’ll have to copy it. It should be easy as it’s only 456 pages…

2). Wait what’s this? Another report on the

↧

In the news

Debate on NSA surveillance with Glenn Greenwald, Alexis Ohanian, Michael Hayden and Alan Dershowitz

Articles from Anatoly Klepov on the compromise of Soviet communications in WWII:

"Historical truth" Beria and Suvorov about cryptography and radiolocation performance - Part 2

Articles from Anatoly Klepov on the compromise of Soviet communications in WWII:

"Historical truth" Beria and Suvorov about cryptography and radiolocation performance - Part 2

↧

↧

Update

I have uploaded TICOM report DF-116-J ‘The German intercept station in Madrid’ – 1948. Available from my Scribd and Google Docs accounts.

↧

The German intercept stations in Spain

In the course of WWII the German signal intelligence agencies intercepted radio traffic from several fixed and mobile stations established throughout Europe. Some of these stations were located in neutral countries and they operated clandestinely, so as not to attract attention from the Allies. Although these stations operated in secrecy the local governments were informed of their existence and had given their tacit approval.

OKW/Chi stations

It was only natural that the Spanish authorities would be worried about Allied spy groups and even more so about the activities of the surviving Republican resistance networks. The civil war had ended only a few years earlier and the supporters of the Republican government could still organize a movement against the regime, especially if they had support from the Allies.

The Spanish government under General Francisco Franco had close ties to Germany, as would be expected considering the support that the Nationalists had received from Germany and Italy during the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39. Without support from Hitler and Mussolini the Nationalists would not have been able to defeat the Republican forces. Yet despite these close ties the position of the Spanish government during WWII was to remain neutral and avoid foreign entanglements.

Even though Spain was neutral the police and the intelligence service cooperated to some extent with the German intelligence services Abwehr and Sicherheitsdienst. In the field of signals intelligence the authorities allowed the establishment of a main radio-intercept station in Madrid and smaller outstations throughout the country. These first of these stations were controlled by the German High Command’s deciphering department – OKW/Chi. OKW/Chi was not the only German agency with radio stations in Spain. In the course of the war a clandestine naval D/F station was added to the OKW/Chi Seville facility and a Luftwaffe intercept station was established in Barcelona. Also in the latter stages of the war the main station in Madrid added a separate section for the Radio Security Service of the Armed Forces- Funkabwehr.

OKW/Chi stations

Information on the OKW/Chi stations is available from several sources such as ‘European Axis Signal Intelligence in World War II’ vol3 and the TICOM reports I-49 and DF-116-J. It should be noted that these sources do not always agree on all the details.

According to these reports the controlling station was established at the German consulate in Madrid (10 Ayala Street) in 1939 or 1940. The commanding officer in the period 1940-1943 was Major von Nida, followed by Lieutenant Eichner up to June 1944 and finally 1st Lieutenant Planker. The codename for the intercept organization in Spain was ‘Stuermer’.There were outstations in the outskirts of Madrid, on a German owned cattle ranch north of Seville, in Tangiers, in Las Palmas, Tenerife and possibly in the Balearic Islands.

The stations were tasked with intercepting traffic from French, Belgian and Portuguese colonies and later traffic from North America and from the British Dominions but did not carry out any codebreaking activities. Instead the coded messages were transmitted back to Berlin.Security measures were strict with all the personnel being told to avoid contact with the locals and even other Germans working at the embassy. The members of the group wore civilian clothes and used at the outstations radio equipment of the American Hallicrafters company. Married men were not allowed to bring their wives to Spain and the unmarried ones were forbidden from marrying Spanish women.

Even so the work of these stations could not remain a secret forever. The Allied authorities occasionally tipped the Spanish police so it could raid these stations but thankfully the Spanish authorities always proceeded with such sluggishness that serious problems were avoided. By the time the police arrived there was nothing compromising for them to find.In the course of the war other German agencies also established covert intercept stations in Spain.

Luftwaffe stationThe signal intelligence service of the Luftwaffe operated an intercept station in Barcelona and it seems that from 1942 they had exclusive control of the entire facility. Flicke in DF-116-J says they had another station near Madrid. According to EASI vol5, p36 they mostly intercepted traffic of the USAAF ferry service.

B-Dienst stationThe naval signal intelligence service B-Dienst (Beobachtungsdienst) operated an intercept station in the same facility in Seville that OKW/Chi was using (or in Barcelona and in the outskirts of Madrid according to DF-116-J). They focused on naval traffic from the Mediterranean and the Atlantic.

Funkabwehr stationThe organizations tasked with monitoring the radio transmissions of illicit operators and spy groups were the Radio Defence Corps of the Armed Forces High Command – OKW Funkabwehr and the similar department of the regular police – Ordnungspolizei. Both agencies operated in occupied Europe but they were assigned different areas.

In late 1942 or early 1943 a special OKW Funkabwehr section was established at the Madrid intercept station. This unit conducted direction finding operations for the radio transmitters of Allied and Spanish Republican spy groups. It seems that they also had a small number of civilian vehicles equipped with mobile D/F devices. According to the study HW 34/2 ‘The Funkabwehr’, p21-22 the Spanish authorities not only allowed the Germans to set up this station but cooperated closely with them in the field of counterintelligence against foreign spies. It was only natural that the Spanish authorities would be worried about Allied spy groups and even more so about the activities of the surviving Republican resistance networks. The civil war had ended only a few years earlier and the supporters of the Republican government could still organize a movement against the regime, especially if they had support from the Allies.

Lieutenant colonel Mettig, who was second in command of OKW/Chi in the period 1943-45 said in TICOM report I-115, p7 that the Funkabwehr station assisted the Spanish General Staff in counterintelligence activities and had good results with traffic from Southern France.

In the course of the war new stations were activated and the Spanish authorities obviously benefited from the German activities, especially in the field of counterintelligence. However as Germany was pushed back by the Allies it was obvious that the war would end with an Allied victory. This influenced the decisions of the Spanish government and in 1944 the Seville, Tangiers and Barcelona stations were closed down. At the end only the Madrid stations remained and they were closed down in 1945, with their equipment turned over to the Spanish authorities and the personnel being repatriated in 1946.

ConclusionThe German signal intelligence agencies operated several clandestine radio-intercept stations in neutral countries during WWII. The close relations between Nazi Germany and Nationalist Spain ensured that the authorities would turn a blind eye on the German intercept activities, especially since some of their results were shared with the Spanish intelligence service.

These stations were valuable to the Germans since they had better reception of local radio traffic from Southern Europe and North Africa. However as the tide of war turned against Germany the Spanish government was forced to follow a policy of ‘strict’ neutrality and most of the stations were closed down.Unfortunately there is limited information available on the performance and setup of these stations in Spain. It is up to Spanish researchers and historians to find more information on this subject.

↧

Codes of the European Economic Community

↧