I’ve added a lot of new information and rewritten parts of Intercepted conversations - Bell Labs A-3 Speech scrambler and German codebreakers. Enjoy!

↧

Mega update of the A-3 essay

↧

More updates

1). In US military attaché codes of WWII I added information from the 1974 interview of Frank Rowlett.

2). In German intelligence on operation Overlord I added information from the postwar interrogation of General Walter Warlimont, deputy chief of the Armed Forces Operations Staff.

2). In German intelligence on operation Overlord I added information from the postwar interrogation of General Walter Warlimont, deputy chief of the Armed Forces Operations Staff.

↧

↧

More information on the codebreakers of the Italian Navy

I’ve added a lot of information from the report ‘Italian Communications Intelligence Organization’-Report by Admiral Maugeri with U.S. Navy Introduction in Italian codebreakers of WWII.

↧

Compromise of Polish communications in WWII – an overview

In WWII Poland fought on the side of the Allies and suffered for it since it was the first country occupied by Nazi Germany. At the end of the war the suffering of the Poles did not end since they had to endure the Soviet occupation of their country and the installation of a communist regime.

5). Polish intelligence/military attaché messages from the Middle East and Bern, Switzerland were read by the Germans throughout the war. For example:

The betrayal of Poland by its Western Allies was a hard blow, especially since its armed forces fought bravely in multiple campaigns. Polish pilots fought for the RAF during the Battle of Britain, Polish troops fought in N.Africa, Italy and Western Europe, the Polish intelligence service operated in occupied Europe and even had agents inside the German high command. Finally the Poles had managed to solve the German Enigma cipher machine in the 1930’s and when they shared the details of their solution with British and French officials in July 1939 they helped them avoid a costly and time consuming theoretical attack on the Enigma.

Considering this impressive success of the Polish cipher bureau one would expect that Polish codes would have a high standard of security and that Polish military, diplomatic and intelligence communications would be secure from eavesdroppers. Surprisingly this was not the case. Even though the Poles periodically upgraded their cipher systems it was possible both for the Germans and the Anglo-Americansto read some of their most secret messages.1). The main Polish diplomatic codes were read in the prewar period and in the years 1940-42.

2). The code used by the Polish resistance movement for communications with the London based Government in Exile was read by the Germans since 1942 (by the agents section of OKH/In 7/VI). 3). The code of the Polish intelligence service in occupied France was solved in 1943 and messages of the ‘Lubicz’ network were read. The book ‘Secret History of MI6: 1909-1949’, p529 says about this group: ‘Some of the Polish networks were very productive. One based in the south of France run by ‘Lubicz' (Zdzislaw Piatkiewicz) had 159 agents, helpers and couriers, who in August and September 1943 provided 481 reports, of which P.5 circulated 346. Dunderdale's other organizations were rather smaller’.

I’m going to cover this case in the future.4). Polish diplomatic/military attache communications on the link Washington-London seem to have been read by the Germans and the British. A German intelligence officer named Zetzsche said in TICOM report I-159 ‘Report on GAF Intelligence based on Interrogation of Hauptmann Zetzsche’, p3

‘Intelligence concerning foreign diplomatic exchanges was received from the Forschungsamt (subordinated directly to GOERING) through Ic/Luftwesen/Abwehr, and was given a restricted distribution. It consisted of intercepted Allied radio-telegrams (e.g. London-Stockholm), ordinary radio reports (e.g. Atlantic Radio) and intercepted traffic between diplomats and ministers on certain links, e.g. Ankara-Moscow (Turks), Bern-Washington (Americans), London-Washington (Poles).10. The last-mentioned source was of great value before and during the invasion and after the breaking-off of Turkish-German relations. In general the Forschungsamt reports contained a great deal of significant information concerning economic and political matters.’

The British also read this traffic as can be seen from messages like the following: Unfortunately there is limited information available on these cases and some very interesting TICOM reports have not been declassified by the NSA yet. Once they are released I will be able to rewrite these essays.

↧

NSA hacks and leaked spy cables

Lots of interesting stories in the news:

Analysis of NSA malware by Kaspersky Lab: ‘Equation Group: The Crown Creator of Cyber-Espionage’.

Compromise of Gemalto, the world’s largest SIM card manufacturer, by NSA and GCHQ: ‘The great SIM heist how spies stole the keys to the encryption castle’.Al Jazeera publishes leaked spy cables from South Africa's State Security Agency (SSA) and its correspondence with ‘the US intelligence agency, the CIA, Britain's MI6, Israel's Mossad, Russia's FSB and Iran's operatives, as well as dozens of other services from Asia to the Middle East and Africa’.

Interesting stuff!

↧

↧

Update

I added the following pic in Italian codebreakers of WWII.

Also in Japanese codebreakers of WWII I added ‘From 1943 onwards the Japanese could solve the Soviet diplomatic code used by the embassies in Seoul, Dairen, and Hakodate for communications with Moscow and Vladivostok’ under the ‘Japanese Army agency’ paragraph and deleted the similar part from the naval agency. The reports I have are from the Japanese army so it would seem that they were responsible for this success.

Also in Japanese codebreakers of WWII I added ‘From 1943 onwards the Japanese could solve the Soviet diplomatic code used by the embassies in Seoul, Dairen, and Hakodate for communications with Moscow and Vladivostok’ under the ‘Japanese Army agency’ paragraph and deleted the similar part from the naval agency. The reports I have are from the Japanese army so it would seem that they were responsible for this success.

↧

More information on the Japanese codebreakers of WWII

I rewrote parts and added lots of pics in Japanese codebreakers of WWII.

↧

Criticism of Soviet/Russian MiG-29 fighter jet

The site foxtrotalpha has an interview with Lt. Col. Fred "Spanky" Clifton and one of the topics discussed was the Russian MiG-29 fighter, introduced in the early 1980’s by the Soviet Air Force. The Mig-29 had aerodynamic performance equal or better to comparable Western aircraft and its R-73 missile coupled with the helmet mounted targeting system were thought to be revolutionary in close combat. Was this evaluation correct or was the performance of this Soviet weapon system exaggerated? Let’s see what the colonel had to say:

What was the MiG-29 Fulcrum like to fly? Did it live up to the fear and Cold War hype?

The Fulcrum is a very simple jet that was designed to fit in the Soviet model of tactical aviation. That means the pilot was an extension of the ground controller. As many have read, innovative tactics and autonomous operations were not approved solutions in the Warsaw Pact countries. The cockpit switchology is not up to western standards and the sensors are not tools used to enhance pilot situation awareness, rather they are only used as tools to aid in the launch of weapons.

The jet is very reliable and fairly simple to maintain. I could service the fuel, oil, hydraulics and pneumatics and had to demonstrate proficiency in these areas before I could take a jet off-station. Its handling qualities are mediocre at best. The flight control system is a little sloppy and not very responsive. This does not mean the jet isn't very maneuverable. It is. I put it between the F-15C and the F-16. The pilot just has to work harder to get the jet to respond the way he wants.

………………………………………………….

The Fulcrum only carries a few hundred more pounds of fuel internally than an F-16. That fuel has to feed two fairly thirsty engines. The jet doesn't go very far on a tank of gas. We figured on a combat radius of about 150 nautical miles with a centerline fuel tank.

…………………………………………………

The radar was actually pretty good and enabled fairly long-range contacts. As already alluded to, the displays were very basic and didn't provide much to enhance the pilot's situational awareness. The radar switchology is also heinous. The Fulcrum's radar-guided BVR weapon, the AA-10A Alamo, has nowhere the same legs as an AMRAAM and is not launch-and-leave like the AMRAAM. Within its kinematic capability, the AA-10A is a very good missile but its maximum employment range was a real disappointment.

One sensor that got a lot of discussion from Intel analysts was the infrared search-and-track system (IRSTS). Most postulated that the MiG-29 could use the passive IRSTS to run a silent intercept and not alert anyone to its presence by transmitting with its radar. The IRSTS turned out to be next to useless and could have been left off the MiG-29 with negligible impact on its combat capability. After a couple of attempts at playing around with the IRSTS I dropped it from my bag of tricks.

Other things that were disappointing about the MiG-29 were the navigation system, which was unreliable, the attitude indicator and the heads-up display.

Overall, the MiG-29 was/is not the 10 foot tall monster that was postulated during the Cold War. It's a good airplane, just not much of a fighter when compared to the West's 4th-generation fighters.

……………………………………………..

During the mid 1990s the US still relied on the relatively narrow field of view AIM-9L/M Sidewinder as a short-range heat-seeking missile, what was it like being introduced to the MiG-29's Archer missile, with its high off bore-sight targeting capabilities and its helmet mounted sight?

The Archer and the helmet-mounted sight (HMS) brought a real big stick to the playground. First, the HMS was really easy to use. Every pilot was issued his own HMS. It mounted via a spring-loaded clip to a modified HGU-55P helmet. The pilot then could connect the HMS to a tester and adjust the symbology so it was centered in the monocle. Once in the jet the simple act of plugging in the power cord meant it was ready to go. There was no alignment process as required with the Joint Helmet-Mounted Cuing System. It just worked.

Being on the shooting end of the equation, I saw shot opportunities I would've never dreamed of with the AIM-9L/M. Those on the receiving end were equally less enthused about being 'shot' from angles they couldn't otherwise train to.

How did a MiG-29 in skilled hands stack up against NATO fighters, especially the F-16 and the F-15?

From BVR (beyond visual range), the MiG-29 is totally outclassed by western fighters. Lack of situation awareness and the short range of the AA-10A missile compared to the AMRAAM means the NATO fighter is going to have to be having a really bad day for the Fulcrum pilot to be successful.

In the WVR (within visual range) arena, a skilled MiG-29 pilot can give and Eagle or Viper driver all he/she wants.

Overall this is a very interesting interview. On the one hand it is impressive that an undeveloped society like the Soviet Union could produce a weapon system that was equal or better than what the West had and also introduced first the revolutionary helmet mounted targeting system. On the other hand it is clear that all Soviet systems suffered from ‘soft’ flaws (poor ergonomics and lack of situation awareness)which limited their performance in the field.

↧

Update

I’ve added links to the CIA FOIA, State Department FOIA and Japan Center for Asian Historical Records websites.

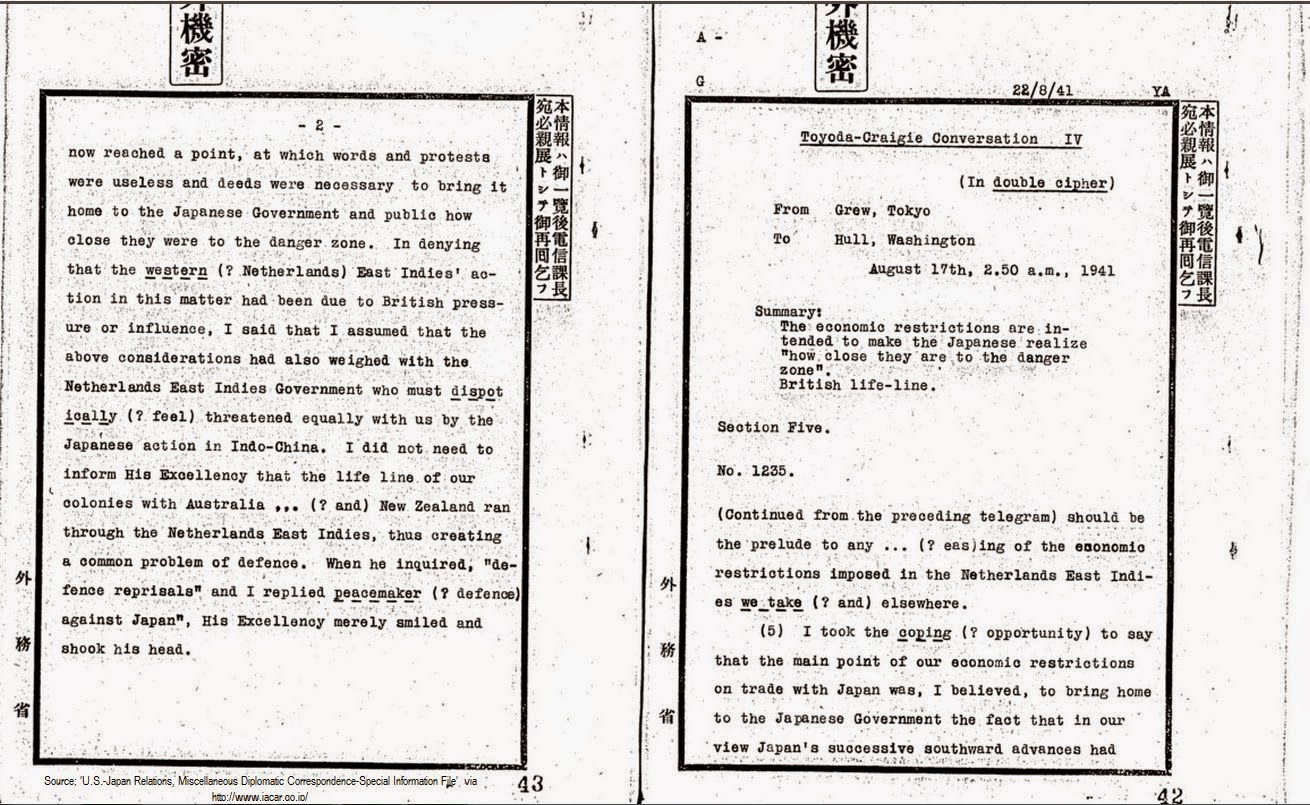

Also added decoded US and British diplomatic messages from 1941 in Japanese codebreakers of WWII. The source was the online archive of the Japan Center for Asian Historical Records. For example:

↧

↧

Article on the Soviet T-34 tank

A very interesting article on the T-34 has been published by ‘The Journal of Slavic Military Studies’. It is ‘Once Again About the T-34’ by Boris Kavalerchik and it’s basically a translation of chapter ‘ЕЩЕ РАЗ О Т -34’ from the book ‘Tankovy udar. Sovetskie tanki v boyakh. 1942-1943’ that I used in my essay ‘WWII Myths - T-34 Best Tank of the war’. If you don’t have a subscription to access the journal you’ll have to purchase the article. It’s expensive but worth it if you’re interested in the real performance of the T-34 tank.

I also added ‘Once Again About the T-34’ in the sources of ‘WWII Myths - T-34 Best Tank of the war’.

↧

The codes of the Polish Intelligence network in occupied France 1943-44

In WWII Poland fought on the side of the Allies and suffered for it since it was the first country occupied by Nazi Germany. In the period 1940-45 the Polish Government in Exile and its military forces contributed to the Allied cause by taking part in multiple campaigns of war. Polish pilots fought for the RAF during the Battle of Britain, Polish troops fought in N.Africa, Italy and Western Europe and the Polish intelligence service operated in occupied Europe and even had agents inside the German High Command.

Although it is not widely known the Polish intelligence service had spy networks operating throughout Europe and the Middle East. The Poles established their own spy networks and also cooperated with foreign agencies such as Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service and Special Operations Executive, the American Office of Strategic Services and even the Japanese intelligence service. During the war the Poles supplied roughly 80.000 reports to the British intelligence services (1), including information on the German V-weapons (V-1 cruise missile and V-2 rocket) and reports from the German High Command (though the agent ‘Knopf’) (2).

In occupied France the intelligence department of the Polish Army’s General Staff organized several resistance/intelligence groups tasked not only with obtaining information on the German units but also with evacuating Polish men so they could serve in the Armed Forces. These networks obviously attracted the attention of the German security services and in 1941 the large INTERALLIE network, controlled by Roman Czerniawski, was dismantled. Another large network was controlled by Zdzislaw Piatkiewicz aka ‘Lubicz'. The book ‘Secret History of MI6: 1909-1949’, p529 says about this group: ‘Some of the Polish networks were very productive. One based in the south of France run by ‘Lubicz' (Zdzislaw Piatkiewicz) had 159 agents, helpers and couriers, who in August and September 1943 provided 481 reports, of which P.5 circulated 346. Dunderdale's other organizations were rather smaller’.

From German and British reports it seems that the radio communications of the Polish spy groups in France (including the ‘Lubicz' net) were compromised in the period 1943-44. Wilhelm Flicke who worked in the intercept department of OKW/Chi (decryption department of the High Command of the Armed Forces) says in ‘War Secrets in the Ether’ (3):The Polish intelligence service in France had the following tasks:

1. Spotting concentrations of the Germany army, air force and navy. 2. Transport by land and sea and naval movements.

3. Ammunition dumps; coastal fortifications, especially on the French coast after the occupation of Northern France. 4. Selection of targets for air attack.

5. Ascertaining and reporting everything which demanded immediate action by the military command. 6. Details regarding the French armament industry working for Germany, with reports on new weapons and planes.

The Poles carried on their work from southern France which had not been occupied by the Germans. Beginning in September 1942 it was certain that Polish agent stations were located in the immediate vicinity of the higher staffs of the French armistice army. In March 1943 German counterintelligence was able to deal the Polish organization a serious blow but after a few weeks it revived, following a reorganization. Beginning the summer of 1943 messages could be read. They contained military and economic information. The Poles in southern France worked as an independent group and received instructions from England, partly by courier, and partly by radio. They collaborated closely with the staff of General Giraud in North Africa and with American intelligence service in Lisbon. Official French couriers traveling between Vichy and Lisbon were used, with or without their knowledge, to carry reports (in the form of microfilm concealed in the covers of books).

The Poles had a special organization to check on German rail traffic to France. It watched traffic at the following frontier points: Trier, Aachen, Saarbrucken, München-Gladbach, Strassburg-Mülhausen and Belfort. They also watched the Rhine crossings at Duisburg, Coblenz, Düsseldorf, Küln, Mannheim, Mainz, Ludwigshafen, and Wiesbaden. Ten transmitters were used for the purpose. All the Polish organizations in France were directed by General Julius Kleeberg. They worked primarily against Germany and in three fields:

1. Espionage and intelligence; 2. Smuggling (personnel);

3. Courier service. Head of the "smuggling service" until 1.6.1944 was the celebrated Colonel Jaklicz, followed later by Lt. Colonel Goralski. Jaklicz tried to penetrate all Polish organizations and send all available man power via Spain to England for service in the Polish Army. The "courier net" in France served the "Civil Delegation", the smuggling net, and the espionage service by forwarding reports. The function of the Civil Sector of the "Civil Delegation" in France was to prepare the Poles in France to fight for an independent Poland by setting up action groups, to combat Communism among the Poles, and to fight against the occupying Germans. The tasks of the military sector of the Delegation were to organize groups with military training to carry on sabotage, to take part in the invasion, and to recruit Poles for military service on "D-Day". The "Civil Delegation" was particularly concerned with Poles in the German O.T. (Organisation Todt) or in the armed forces. It sought to set up cells which would encourage desertion and to supply information.

Early in 1944 this spy net shifted to Northern France and the Channel Coast. The Poles sought to camouflage this development by sending their messages from the Grenoble area and permitting transmitters in Northern France to send only occasional operational chatter. The center asked primarily for reports and figures on German troops, tanks and planes, the production of parts in France, strength at airfields, fuel deliveries from Germany, French police, constabulary, concentration camps and control offices, as well as rocket aircraft, rocket bombs and unmanned aircraft. In February 1944 the Germans found that Polish agents were getting very important information by tapping the army telephone cable in Avignon.

In March 1944, the Germans made a successful raid and obtained important radio and cryptographic material. Quite a few agents were arrested and the structure of the organization was fully revealed. Beginning early in June, increased activity of Polish radio agents in France became noticeable. They covered German control points and tried to report currently all troop movements. German counterintelligence was able to clarify the organization, its members, and its activity, by reading some 3,000 intercepted messages in connection with traffic analysis. With the aid of the Security Police preparations were made for the action "Fichte" which was carried out on 13 July 1944 and netted over 300 prisoners in all parts of France.

This, together with preliminary and simultaneous actions, affected: 1. The intelligence service of the Polish II Section,

2. The smuggling service, 3. The courier service with its wide ramifications.

The importance of the work of the Poles in France is indicated by the fact that in May 1944 Lubicz and two agents were commended by persons very high in the Allied command "because their work was beginning to surpass first class French sources." These agents had supplied the plans of all German defense installations in French territory and valuable details regarding weapons and special devices.Flicke’s statements on the solution of Polish intelligence codes in 1943 can be confirmed, in part, by the postwar interrogation of Oscar Reile, head of Abwehr counterintelligence in occupied France. In his report 'Notes on Leitstelle III West Fur Frontaufklarung' (4) he said about the Polish intelligence communications:

CODE-CRACKING BY FUNKABWEHR107. Leitstelle III West also benefited from the work done by the code and cipher department of Funkabwehr, which studied all captured documents connected with codes and ciphers, with the object of decoding and deciphering the WT traffic of agents who were regarded as important and could not be captured.

108. Valuable results were often obtained by Funkabwehr. During the winter of 43/44, the above-mentioned code and cipher department succeeded in breaking codes used by one of the most important transmitters of the Polish Intelligence Service in FRANCE. For months thereafter WT reports from Polish agents to ENGLAND were intercepted and understood; the same applied to orders they received from ENGLAND. The Germans also learnt that important military plants were known to the Allies, and a considerable number of names and cover names of members of the Polish Intelligence Service were discovered.Flicke also said ‘Early in 1944 this spy net shifted to Northern France and the Channel Coast. The Poles sought to camouflage this development by sending their messages from the Grenoble area and permitting transmitters in Northern France to send only occasional operational chatter’. This statement can also be confirmed by other German and British reports.

The monthly reports of Referat 12 (Agents section) of the German Army’s signal intelligence agency OKH/In 7/VI (5) mention spy messages from Grenoble in May and July 1943 as links top and 71c (9559, Grenoble), so it is possible that these are the Polish intelligence messages that Flicke says were solved in summer 1943. Unfortunately these reports are difficult to interpret since they use codewords for each spy case.More information is available from messages found in the captured archives of OKW/Chi (since Chi also worked on Polish military intelligence codes). The British report DS/24/1556 of October 1945 (6) shows that messages on the link London-Grenoble were solved and these were enciphered with the military attaché cipher POLDI 4.

The same report mentions that in August 1944 the British authorities became aware that decoded Polish military intelligence messages from Grenoble were sent from Berlin to the Abwehr station in Madrid, Spain:

‘In August 1944, a series of decoded Polish ‘Deuxieme Bureau’ messages between London and Grenoble were seen by us in ISK traffic being forwarded by Berlin to Abwehr authorities at Madrid. The time lags varied between 5 and 43 days. S.L.C. Section at headquarters informed us that this was a properly controlled leakage, and that no cypher security action was necessary or desirable.’Some of these messages can be found in the British national archives (7):

It is interesting to note that the response of the higher authorities was ‘this was a properly controlled leakage, and that no cypher security action was necessary or desirable’, without however giving more details.

Conclusion

During WWII the Polish intelligence service operated throughout Europe and was able to gather information of great value for the Western Allies. These activities were opposed by the security services of Nazi Germany and in this shadow war many Allied spy networks were destroyed and their operatives imprisoned or killed. In their operations against Allied agents the Germans relied not only on their own counterintelligence personnel but also signals intelligence and codebreaking. Fixed and mobile stations of the Radio Defense Corps (Funkabwehr) monitored unauthorized radio transmissions and through direction finding located their exact whereabouts. The Agents section of Inspectorate 7/VI and OKW/Chi analyzed and decoded enciphered agents messages, with the results passed to the security services Abwehr and Sicherheitsdienst. Both agencies solved Polish intelligence communications including traffic from Switzerland, France, Poland, the Middle East and other areas. The Polish intelligence networks in France were an important target for the Germans not only because they were a security risk but also because they would undoubtedly assist the Allied troops in their invasion of Western Europe in 1944. In that sense the compromise of the communications of the Polish military intelligence network was an important success since it allowed the Germans to dismantle parts of this group and also learn of what the Allied authorities wanted to know about German strengths and dispositions in France.

According to Flicke the success started in summer 1943 and from the British reports we can see that they continued to solve the traffic till summer ’44 (when France was liberated). It is not clear of when the Brits first learned that the Polish communications had been compromised and what measures they took to prevent the leakage of sensitive information. It is also not clear of whether they chose to inform the Poles about all this…Notes:

(1). Journal of U.S. Intelligence Studies article: ‘England's Poles in the Game: WWII Intelligence Cooperation’(2). War in History article: ‘Penetrating Hitler's High Command: Anglo-Polish HUMINT, 1939-1945’

(3). ‘War Secrets in the Ether’, p230-1(4). CSDIC SIR 1719 - 'Notes on Leitstelle III West Fur Frontaufklarung', p15

(5). War Diary of OKH/In 7/VI - May and July 1943(6). British national archives HW 40/222

(7). British national archives HW 40/221Sources: ‘Secret History of MI6: 1909-1949’, Journal of U.S. Intelligence Studies article: ‘England's Poles in the Game: WWII Intelligence Cooperation’, ‘War Secrets in the Ether’, CSDIC SIR 1719 - 'Notes on Leitstelle III West Fur Frontaufklarung', HW 40/221 ‘Poland: reports and correspondence relating to the security of Polish communications’, HW 40/222 ‘Poland: reports and correspondence relating to the security of Polish communications’, War in History article: ‘Penetrating Hitler's High Command: Anglo-Polish HUMINT, 1939-1945’, War Diary of OKH/In 7/VI

↧

Who was source 206?

During WWII the US Office of Strategic Services station in Bern, Switzerland (headed by Allen Dulles) recruited agents in occupied Europe and transmitted intelligence reports back to Washington. Dulles collaborated in intelligence gathering activities with Gerald Mayer, local representative of the Office of War Information and General Barnwell Legge, US military attaché to Switzerland.

Some of these reports were decoded by the Germans and the Finns and we can see that they mention specific agents.

For example message No. 73 Bern-London of 4/4/1943, by General Legge lists several German divisions stationed in France and says that the information came from Source 206. Who was this mysterious agent? ↧

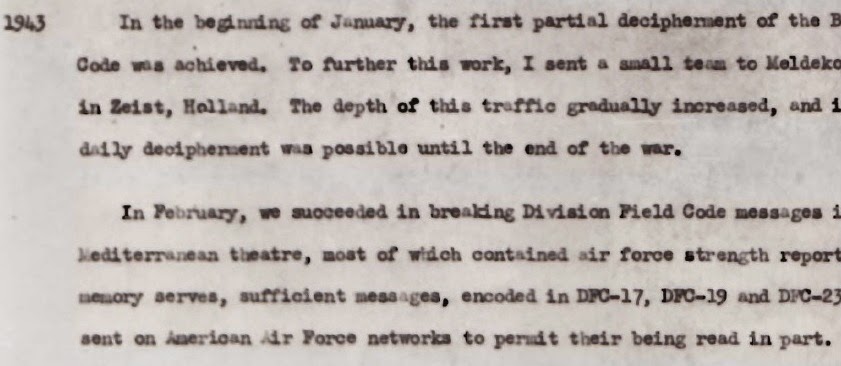

The US Division Field Code

When the United States entered WWII, in December 1941, US military and civilian agencies were using several cryptologic systems in order to protect their sensitive communications. The Army and Navy only had a small number of SIGABAcipher machines so they had to rely on older systems such as the M-94/M-138 strip ciphers and on codebooks such the War Department Telegraph Code, the Military Intelligence Code and the War Department Confidential Code.

The Luftwaffe’s Chi Stelle was also interested in the DFC and according to Dr. Ferdinand Voegele, the Luftwaffe's chief cryptanalyst in the West, USAAF messages from the Mediterranean area were read (4).

The solution of these messages allowed the Germans to identify the 29th Infantry Division and considering the unit’s rule during operation Overlord it is possible that they gave the Germans vital clues about the upcoming invasion of France.

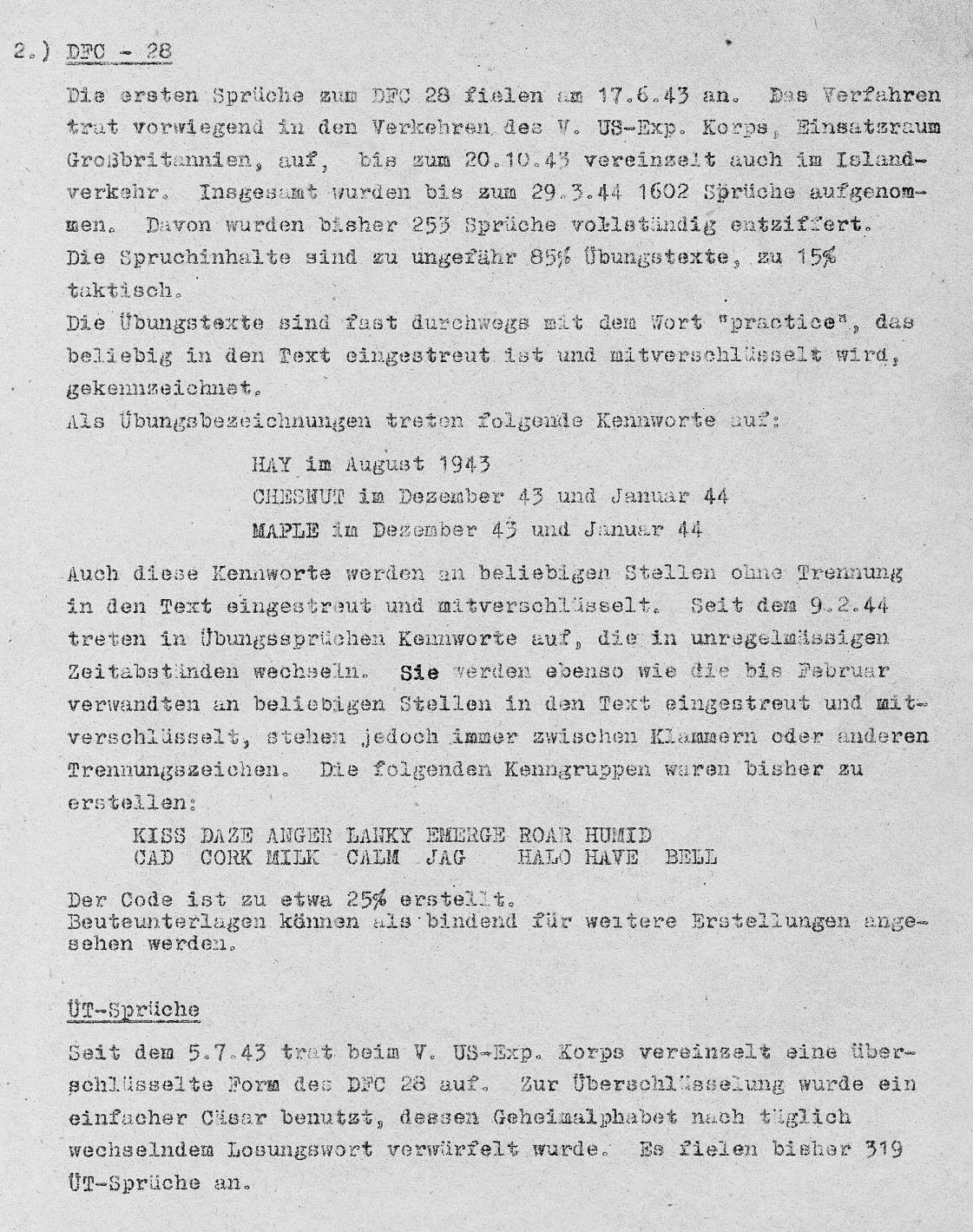

Another system prepared for the Army was the Division Field Code. This was a 4-letter codebook of approximately 10.000 groups and in the 1930’s several editions were printed by the Signal Intelligence Service (1). However the introduction of the SIGABA and especially the M-209 cipher machine made this system obsolete. Still it seems that the DFC was used on a limited scale, during 1942-44, by the USAAF and by US troops stationed in Iceland and the UK.

Examples of DFC training edition No 2:Solution of DFC by German codebreakers

The German Army and AF signal intelligence agencies were able to exploit this outdated system and they read US military messages from Iceland, Central America, the Caribbean and Britain. Most of the work was done by field units, specifically the Army’s fixed intercept stations (Feste Nachrichten Aufklärungsstelle) Feste 9 at Bergen, Norway and Feste 3 at Euskirchen, Germany.According to Army cryptanalyst Thomas Barthel several editions of the Division Field Code were read, some through physical compromise (2):

The DFCs (Divisional Field Codes).

(a). DFC 15In use in autumn 42, broken in Jan 43. Traffic was intercepted on a frequency of 4080 Kos from US Army links in ICELAND (stas at REYKJAVIK, AKUREYRI and BUDAREYRI). Stas used fixed call-signs till autumn 43, and thereafter daily call -signs. This field code was current for one month only. It was a 4-letter code, non-alphabetical, with variants and use of "duds" (BLENDERN). It was broken by assuming clear routine messages were the basis of the encoded text, such as Daily Shipping Report, Weather Forecast etc.

(b) DFC 16 This was current for one month, probably in Nov 42. It was similar to the DFC 15 above.

(c) DFC 17This was current from Dec 42 to Feb 43. About the latter date one or two copies of the table were captured. Very good material was intercepted from ICELAND, also from 6 (?) USAAF links in Central America, Caribbean Sea etc. Traffic was broken and read nearly up to 100%.

(d) DFC 21This succeeded the DFC 17. Results were the same.

(e) DFC 25Current only in CARIBBEAN SEA area, and read in part.

(f) DFC 28 This succeeded the DFC 21 in summer 43. It was used by the ICELAND links and the 28 (or 29) US Div in the South of ENGLAND. The code was read, Now and again it was reciphered by means of alphabet substitution tables ("eine Art von Buchstabentauschtafel") changing daily. This method was broken because the systematic construction of the field code was known.

(g) DFC 29A copy of this table was captured in autumn 43. It was never used, PW did not know why.

The War Diary of the German Army’s signal intelligence agency OKH/In 7/VI shows that the DFC was called AC 6 (American Code 6) and several editions were solved in the period 1943-44. Most of the processing was left to field units, with only a few messages solved by Referat 1 (USA section) of Inspectorate 7/VI. The report of March 1943 says that the captured specimen DFC 17 could be used to solve the preceding and following versions (since they were constructed in the same way) and it showed that the code values retrieved by field units and the central department through cryptanalysis were mostly correct (3).

The 29th Infantry Division and the invasion of Normandy

In 1943 the M-209 cipher machine replaced the M-94 strip cipher as the standard crypto system used at division level by the US Army, however older systems like the DFC continued to be used for training purposes. The US military forces in Britain took part in many exercises during the latter part of 1943 and early 1944, since they were preparing for the invasion of Western Europe and some of their training messages were sent on the 28th edition of the Division Field Code. These messages were intercepted and decoded by the German Army’s KONA 5 (Signals Intelligence Regiment 5), covering Western Europe. NAAS 5 was the cryptanalytic centre of KONA 5 and its quarterly reports (5) show that training messages from the US V Expeditionary Corps and the 29th Infantry Division were solved.

Notes:

(1). Rowlett-1974 and Kullback-1982 NSA oral history interviews(2). CSDIC/CMF/Y 40 – ‘First Detailed Interrogation on Report on Barthel Thomas

(3).War diary Inspectorate 7/VI - March 1943(4). TICOM IF-175 Seabourne Report, Vol XIII, p9 and 16.

(5). E-Bericht der NAASt 5 Nr 1/44 and Nr 2/44.Sources: Frank Rowlett NSA oral history interview - 1974, Solomon Kullback NSA oral history interview - 1982, CSDIC/CMF/Y 40 – ‘First Detailed Interrogation on Report on Barthel Thomas’, War diary Inspectorate 7/VI, War diary NAAS 5, TICOM IF-175 Seabourne Report, Vol XIII ‘Cryptanalysis within the Luftwaffe SIS’, DFC training edition No 2.

Acknowledgments: I have to thank Rene Stein of the National Cryptologic Museum for the Rowlett and Kullback interviews and Mike Andrews for the DFC pics.

↧

↧

NAAS 5 reports retrieved from France - 1945

During WWII the German Army’s signal intelligence agency OKH/In 7/VI had signal intelligence regiments assigned to Army Groups in order to supply them with radio intelligence on Allied formations. Western Europe was covered by KONA 5 (Signals Intelligence Regiment 5), whose cryptanalytic centre NAAS 5 (Nachrichten Aufklärung Auswertestelle - Signal Intelligence Evaluation Center) was based in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, a suburb of Paris.

In summer 1944 the Germans had to evacuate France and it seems that this unit tried to destroy some of its reports but they didn’t have time to properly dispose of them. Instead many reports were buried.

The US authorities were able to locate the site and they recovered many of these documents. A US report, dated 25 January 1945, says that about 2.000 sheets of paper were recovered and were 30% readable. They included intercepts and decrypts of the M-209 cipher machine, the War Department Telegraph Code, possibly Combined Cipher Machine traffic, as well as the British Aircraft movement’s Code and Syko system.There was even a message from Washington to the US Military Mission in China from 1942 sent via the gunboat TUTUILA.

↧

The unscrupulous Italian official and the code of colonel Fellers

One of the most damaging compromises of Allied communications security, during WWII, was the case of Colonel Bonner Fellers, US military attaché in Cairo during 1940-2. Fellers sent back to Washington detailed reports concerning the conflict in North Africa and in them he mentioned morale, the transfer of British forces, evaluation of equipment and tactics, location of specific units and often gave accurate statistical data on the number of British tanks and planes by type and working order. In some cases his messages betrayed upcoming operations.

Fellers used the Military Intelligence Code No11, together with substitution tables. The Italian codebreakers had a unit called Sezione Prelevamento (Extraction Section). This unit entered embassies and consulates and copied cipher material. In 1941 they were able to enter the US embassy in Rome and they copied the MI Code No11. A copy was sent to their German Allies, specifically the German High Command's deciphering department – OKW/Chi. The Germans got a copy of the substitution tables from their Hungarian allies and from December 1941 they were able to solve messages. Once the substitution tables changed they could solve the new ones since they had the codebook and they could take advantage of the standardized form of the reports. Messages were solved till 29 June 1942 and they provided Rommel with so much valuable information that he referred to Fellers as his ‘good source’.

The British realized that a US code was being read by the Germans when they, in turn, decoded German messages containing information that could only have come from the US officials in Egypt. The Americans however were not easily convinced that their representative’s codes had been ‘broken’ and it took them months before they changed Colonel Fellers code.The Germans didn’t know that the Brits had solved messages enciphered on their Enigma machine and thus had different ideas about who betrayed their codebreaking success. Wilhelm Flicke, who worked in the intercept department of OKW/Chi wrote in TICOM report DF-116-Z about this case:

During the war there was stationed at the Vatican a diplomatic representative of the U.S.A. who stood in radio communications with Washington like any other ambassador or minister. In a radiogram sent to Washington in June 1942, enciphered by means of a diplomatic code book, one could read of a conversation which representative of the Vatican had had with an Italian of high position. During this conversation the Italian had mentioned that the Germans could read the most important cryptographic system of the American Military Attaché. The American representative had learned this at the Vatican through a Vatican official and was therefore warning the American War Department against any further use of this cryptographic system.Weisser (a cryptanalyst of OKW/Chi) also said that it was the Italians who betrayed the German success in his report TICOM I-201:

Did the Germans have a reason to mistrust their Italian allies?

It seems that the answer is yes. On July 24 1942 Leland B. Harrison, US ambassador to Switzerland, sent a telegram to assistant secretary Gardiner Howland Shaw (who was in charge of the State Departments cipher unit) warning him that an Italian official had met with Harold Tittmann (US representative to the Vatican) and had told him that the US diplomatic code used by the embassy in Egypt was compromised.↧

Friedman collection released by NSA

The NSA has released a huge collection of documents relating to William Friedman. Their statement says:‘This collection, composed of over 52,000 pages in more than 7,600 documents, including some sound recordings and photographs, has been preserved in the NSA Archives for its historic significance and value. The bulk of the material dates from 1930–1955 and represents Mr. Friedman’s work at the Signals Intelligence Service, the Signal Security Agency , the Armed Forces Security Agency, and NSA’.

Study of decoded State Department messages (very interesting…)

Japanese telegram containing decode of US attaché message and the original

American Consul in Madras, India complains about the new cipher machine M-325

TICOM DF list

Work done on TICOM material by AFSA

OTTICO MECCANICA ITALIANA cipher machine

Special conference on M-209 security – 1950 (even in 1950 Friedman didn’t know about the work of NAAS 5 and their decoding device)

Interrogation of Vassalio Todaro

Interrogation of two Italian signals personnel

War histories list

You can search their database for specific reports. Here are the links to some files that I found interesting:

Security of our high-grade cryptographic systems - 1945Study of decoded State Department messages (very interesting…)

Japanese telegram containing decode of US attaché message and the original

American Consul in Madras, India complains about the new cipher machine M-325

TICOM DF list

Work done on TICOM material by AFSA

OTTICO MECCANICA ITALIANA cipher machine

Special conference on M-209 security – 1950 (even in 1950 Friedman didn’t know about the work of NAAS 5 and their decoding device)

Interrogation of Vassalio Todaro

Interrogation of two Italian signals personnel

Italian official informs State Department of code compromise in Cairo (mentioned by Flicke in ‘War Secrets in the Ether’)

Security of Allied Ciphers – 25 August 1945 (contains Soviet intelligence messages from Harbin embassy)War histories list

↧

The compromise of the communications of General Barnwell R. Legge, US military attache to Switzerland

In the course of WWII both the Allies and the Axis powers were able to gain information of great value from reading their enemies secret communications. In Britain the codebreakers of Bletchley Park solved several enemy systems with the most important ones being the German Enigma and Tunnycipher machines and the Italian C-38m. Codebreaking played a role in the Battle of the Atlantic, the North Africa Campaign and the Normandy invasion. In the United States the Army and Navy codebreakers solved many Japanese cryptosystems and used this advantage in battle. The great victory at Midway would probably not have been possible if the Americans had not solved the Japanese Navy’s code.

On the other side of the hill the codebreakers of Germany, Japan, Italyand Finlandalso solved many important enemy cryptosystems both military and diplomatic. The German codebreakers could eavesdrop on the radio-telephone conversations of Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, they could decode the messages of the British and US Navies during their convoy operations in the Atlanticand together with the Japanese and Finns they could solve State Department messages (both lowand highlevel) from embassies around the world.

The State Department made many mistakes in the use of its cipher systems and thus compromised not only US diplomatic communications but also the messages of other organizations that were occasionally enciphered with State Department systems, such as the Office of Strategic Services and the Office of War Information. Another similar case concerns the communications of General Barnwell R. Legge, US military attache to Switzerland during WWII. Legge was a veteran of WWI and recipient of the Distinguished Service Cross. In Switzerland he worked to promote US interests and he also cooperated in intelligence gathering activities with Allen Dulles, head of the local station of the Office of Strategic Services. The Swiss were officially neutral but they had close economic relations with the Axis countries and thus it was possible for the Allied intelligence agencies to gather information on political and military developments in Europe. Legge sent reports dealing with military developments and Axis war potential to the War Department in Washington but it seems that at least some of them were also read by the Germans and the Finns.

US military attaches used several cryptosystems during WWII. The basic systems were the Military Intelligence Code and the War Department Confidential Code. These were letter codebooks enciphered with the use of substitution tables. The US authorities were confident in their security but in 1941-42 the Italians and the Germans were able to get copies of the codebooks and some of the substitution tables and thus they could read US attache communications from Stockholm, Moscow, Cairo, Baghdad, Teheran and possibly other areas. The communications of colonel Bonner Fellers, US military attache in Cairo during 1940-2, were very important for the Germans and they provided them with valuable information during the fighting in N. Africa.It is reasonable to assume that General Legge also used these codebooks at least in the period 1941-42 but it’s clear that he also had the M-138-A strip cipher and in late 1944 he was given one time pads. A report found in the US National Archives and Records Administration (1) has the results of a security study of his messages sent in the period April-June 1944. The system he was using was the strip cipher and the report says ‘While many violations were found in the traffic, it may be concluded that security has been maintained because of the relatively small number of groups enciphered each day’.

From the information available at this timeit seems that, with one exception, messages enciphered with his systems were not read by the Axis powers. The exception seems to have been messages sent in early 1943. In 1943 the German codebreakers were solving the messages of the US embassy in Bern, Switzerland, so it is possible that they also solved some of Legge’s messages cryptanalytically. It is also possible that his cipher system was compromised in another way. According to ‘Operatives, Spies, and Saboteurs: The Unknown Story of the Men and Women of World War II's OSS’ (2) a janitor working at the US embassy in Bern was a German spy and while going through the trash he found discarded copies of messages that he passed on to the Germans. The Germans could have used these messages to solve Legge’s cryptosystem (plaintext-ciphertext compromise). The compromise of messages in early 1943, is confirmed from decoded US messages found in the Finnish national archives, in collection T-21810/4. A few messages signed Legge are available for March and April ’43. The originals are from NARA, collection RG 319 'Records of the Army Staff'.

Other US messages from Bern, found in the Finnish national archives, have information on German war production and mobilization data. Although these are not signed Legge they must have originated either from his office or from the OSS station. These messages were enciphered with State Department systems that the Germans and the Finns could solve cryptanalytically. So even if US attache ciphers were secure it was still possible for the Axis powers to read some of Legge’s communications in the period 1943-44. For example message No 4.926 of August 1st 1944 and the original from NARA, collection RG 59:

Also message No. 4973 of August 3rd 1944 and the original from NARA, collection RG 59:

Notes:

(1) NARA - collection RG 457 - Entry 9032 - box 1.019 - ‘Working papers on strip cipher systems, 1943-1947’(2) ‘Operatives, Spies, and Saboteurs: The Unknown Story of the Men and Women of World War II's OSS’, p77

Acknowledgments: I have to thank Randy Rezabek of TICOM Archive for the strip cipher security report.

↧

↧

Update

1). The following reports are available from the NSA’s website:

Flicke vol2

Interrogation of Samarughi, Giuseppe

Interrogation of Augusto Bigi

Flicke vol2

Interrogation of Samarughi, Giuseppe

Interrogation of Augusto Bigi

I’ve also added them in my TICOM collection (both google drive and scirbd).

2). I added the following paragraph in German intelligence on operation Overlord:

Division Field Code of the 29th Infantry DivisionThe US Division Field Code was a 4-letter codebook of approximately 10.000 groups, used primarily for training purposes. In 1944 the 29th Infantry Division, stationed in the UK, was using the 28th edition of the DFC for training messages. Some of these messages were solved by NAAS 5 which was the cryptanalytic centre of KONA 5 (Signals Intelligence Regiment 5), covering Western Europe. The reports of that unit show that these decoded messages allowed the Germans to identify the 29th Infantry Division and considering the unit’s rule during operation Overlord it is possible that they gave the Germans vital clues about the upcoming invasion of France.

3). I added the following paragraph in US military attaché codes of WWII:

It seems that both were referring to a telegram sent on July 24 1942 by Leland B. Harrison, US ambassador to Switzerland, to assistant secretary Gardiner Howland Shaw (who was in charge of the State Departments cipher unit) warning him that an Italian official had met with Harold Tittmann (US representative to the Vatican) and had told him that the US diplomatic code used by the embassy in Egypt was compromised. The Germans obviously solved this message and thus attributed the end of the Fellers telegrams to Italian treachery. However looking at the dates it’s clear that this was not true. Fellers changed his cryptosystem in June 1942, while this telegram was sent in July.4). I added the following links in Italian codebreakers of WWII:

CSDIC/CMF/Y 29‘First detailed interrogation of Samarughi, Giuseppe’, CSDIC/CMF/Y 4‘First detailed interrogation of Bigi, Augusto’, CSDIC (main)/ Y 12 ‘First detailed interrogation of Vassalio Todaro’

↧

Awesome!

This doesn’t have anything to do with WWII or codes and ciphers but it’s too awesome not to upload (provided you watch the show)

↧

The OSS Bern station and the compromise of State Department codes in WWII

In the course of WWII both the Allies and the Axis powers were able to gain information of great value from reading their enemies secret communications. In Britain the codebreakers of Bletchley Park solved several enemy systems with the most important ones being the German Enigma and Tunny cipher machines and the Italian C-38m. Codebreaking played a role in the Battle of the Atlantic, the North Africa Campaign and the Normandy invasion. In the United States the Army and Navy codebreakers solved many Japanese cryptosystems and used this advantage in battle. The great victory at Midway would probably not have been possible if the Americans had not solved the Japanese Navy’s code.

On the other side of the hill the codebreakers of Germany, Japan, Italy and Finland also solved many important enemy cryptosystems both military and diplomatic. The German codebreakers could eavesdrop on the radio-telephone conversations of Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, they could decode the messages of the British and US Navies during their convoy operations in the Atlantic and together with the Japanese and Finns they could solve State Department messages (both low and high level) from embassies around the world.

The M-138-A strip cipher was the State Department’s high level system and it was used extensively in the period 1941-44. Although we still don’t know the full story the information available points to a serious compromise both of the circular traffic (Washington to all embassies) and special traffic (Washington to specific embassy) in the period 1941-44. In this area there was cooperation between Germany, Japan and Finland. The German success was made possible thanks to alphabet strips and key lists they received from the Japanese in 1941 and these were passed on by the Germans to their Finnish allies in 1942. The Finnish codebreakers solved several diplomatic links in that year and in 1943 started sharing their findings with the Japanese. German and Finnish codebreakers cooperated in the solution of the strips during the war, with visits of personnel to each country. The Axis codebreakers took advantage of mistakes in the use of the strip cipher by the State Department’s cipher unit.Apart from diplomatic messages their success against the strip cipher also allowed them to read some OSS -Office of Strategic Services messages from the Bern station. The compromise of OSS traffic did not remain secret for long. In 1943 Allen Dulles (head of the OSS Bern station) received word from Admiral Canaris and General Schellenbergthat his communications had been compromised and in addition the German officials Hans Bernd Giseviusand Fritz Kolbe showed him actual decoded US messages. It’s not clear what measures the US authorities took to protect their communications but the diplomatic traffic continued to be read by the Germans and the Finns in the period 1943-44. It seems that the US authorities attributed the German success to physical compromise (probably a spy in the embassy) and thus didn’t realize that their ciphers could be solved cryptanalytically. They would realize how wrong they were in late 1944 when more information became available on the compromise of State Department codes and ciphers.

In September 1944 Finland signed an armistice with the Soviet Union. The people in charge of the Finnish signal intelligence service anticipated this move and fearing a Soviet takeover of the country had taken measures to relocate the radio service to Sweden. This operation was called Stella Polaris (Polar Star). In late September roughly 700 people, comprising members of the intelligence services and their families were transported by ship to Sweden. The Finns had come to an agreement with the Swedish intelligence service that their people would be allowed to stay and in return the Swedes would get the Finnish crypto archives and their radio equipment. At the same time colonel Hallamaa, head of the signals intelligence service, gathered funds for the Stella Polaris group by selling the solved codes in the Finnish archives to the Americans, British and Japanese.The Finns revealed to the American representatives that they had solved several State Department codes and could read the messages from a number of embassies including Berne (Carlson-Goldsberry report). Obviously the OSS leadership was interested in finding out whether OSS communications passing over diplomatic links were also read.

Unfortunately the relevant files in the OSS collection do not reveal the final outcome of this investigation.

It seems that during the same period the OSS received more concrete evidence regarding the compromise of the communications of the Bern embassy. In the US National Archives and Records Administration, RG 226 ‘Records of the Office of Strategic Services’ - Entry 123 there are intelligence reports from Bern received in late 1944. Some of them contain summaries of decoded US messages of the Bern embassy that must have come from German reports given to the OSS by members of the German Resistance (probably Gisevius and Kolbe). For example:Sources: NARA-RG 226-entry 123-Bern-SI-INT-29 -Box 3-File 34 ‘German intelligence, Hungary’, ‘Hitler, the Allies, and the Jews’

↧